Immigration Law Considerations

Part II: Who is a “long-term” lawful permanent resident (“LPR”) and why does it matter?

A post in August 2014 explained the basic rule of who is a “long-term resident” as that technical term is defined for tax purposes in IRC Section 877 (e)(2). There is much confusion about how the tax law defines a “lawful permanent resident” (“LPR”) versus  how immigration law defines what is almost the same concept. The statutes are different and have definitions in two separate federal codes (Title 26, the federal tax provisions and Title 8, the immigration law provisions).

how immigration law defines what is almost the same concept. The statutes are different and have definitions in two separate federal codes (Title 26, the federal tax provisions and Title 8, the immigration law provisions).

See –

Who is a “long-term” lawful permanent resident (“LPR”) and why does it matter?

Posted on August 19, 2014

This follow-up comment is to highlight some key concepts about why it matters if you become a “long-term” resident as that term is defined in the tax law.

- A LPR can reside for substantially shorter periods in the U.S. (shorter than the apparent 7 or 8 years identified in the statute), and still be a “long-term resident” per IRC Section 877 (e)(2) depending upon the facts of any particicular case.

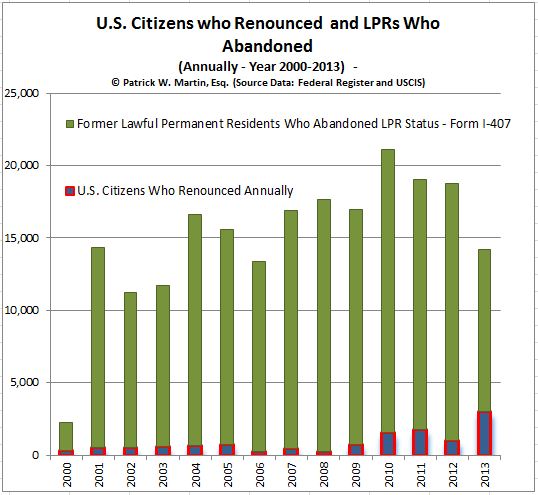

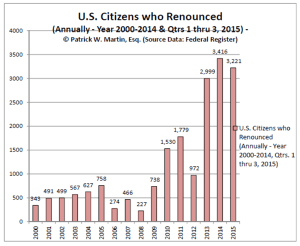

- There are far more LPRs who abandon their status (formally) than U.S. citizens who formally take the oath of renunciation. See the table above reflecting those who have formally renounced U.S. citizenship versus those who have formally abandoned their LPR status.

- Plenty of LPRs informally abandon their LPR status for immigration purposes by moving and living permanently outside the U.S.

- An individual who has/had LPR status, has no control over the timing of when their status ends; if it is determined to have been legally abandonmened by a federal immigration judge. See, The dangers of becoming a “covered expatriate” by not complying with Section 877(a)(2)(C).

- There are plenty of timing issues for LPRs surrounding how and when they have “abandoned” their LPR status for purposes of IRC Section 877 (e)(2). See –

Timing Issues for Lawful Permanent Residents (“LPR”) Who Never “Formally Abandoned” Their Green Card, Posted on August 15, 2015

Survey of the Law of Expatriation from 2002: Department of Justice Analysis (Not a Tax Discussion)

Most discussions regarding renunciation/relinquishment of U.S. citizenship are highly focused towards the U.S. federal tax consequences. Today, the focus is on a 2002 report prepared by the DOJ for the Solicitor General, who supervises and conducts government litigation in the United States Supreme Court.

The report is found here, and I have highlighted some key excerpts: Survey of the Law of Expatriation: Department of Justice Analysis:

* * *

Part II: C’est la vie Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle! Tax Timing Problems for Former U.S. Citizens is Nothing New – the IRS and the Courts Have Decided Similar Issues in the Past (Pre IRC Section 877A(g)(4))

This is Part II, a follow-on discussion of older U.S. case law and IRS rulings that address how and when individuals are subject to U.S. taxation before and after they assert they are no longer U.S. citizens.

I might point out that I am of the belief that we humans always like to hear the news we want to hear; and/or interpret it in the way we find most beneficial to us. Who doesn’t like good news versus bad news? Whether we (laypeople and tax lawyers alike) interpret Section 877A(g)(4) in any particular way; it is of no real consequence when it is the IRS that will enforce the law and ultimately the Department of Justice, Tax Division who will handle any such case interpreting this provision before a U.S. District Court or the Court of Federal Claims. For those who have not litigated before these Courts and seen how aggressive are the government lawyers in advocating for the government, the following discussion will hopefully be illustrative.

See, Part I: Tax Timing Problems for Former U.S. Citizens is Nothing New – the IRS and the Courts Have Decided Similar Issues in the Past (Pre IRC Section 877A(g)(4)), dated October 16, 2015.

The question is what is the correct date of “relinquishment of citizenship” as defined in the statute; IRC Section 877A(g)(4)? Many argue the law cannot be applied retroactively?

However, the specific case discussed here, did just that; applied the law retroactively to determine U.S. citizenship status of an individual and corresponding tax obligations. This was also in a time of a much simpler tax code with (i) no international information reporting requirements (e.g., IRS Forms 8938, 8858, 5471, 8865, 3520, 3520-A, 926, 8621, etc.), (ii) no Title 31 “FBAR” reporting requirements and (iii) no constant drumbeat by the IRS of international taxpayers and enforcement. See, recent announcement by IRS on Oct. 16, 2015 (one day after tax returns were required to be filed by many) Offshore Compliance Programs Generate $8 Billion; IRS Urges People to Take Advantage of Voluntary Disclosure Programs. However, for cautionary posts on the IRS OVDP and the deceptive numbers published (e.g., “$8 Billion”), see How is the offshore voluntary disclosure program really working? Not well for USCs and LPRs living overseas posted May 10, 2014 and The 2013 GAO Report of the IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, International Tax Journal, CCH Wolters Kluwer, January-February 2014. PDF version here.

Of course, the answer to this question helps determine if and when will the individual be subject to the federal tax laws of the U.S. on their worldwide income and global assets. In the case of Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle (an interesting 1977 appellate opinion from the firs circuit) she had spent little time in the U.S. and had sent a letter in her native language French to the U.S. Department of State, which stated “I have never considered myself to be a citizen of the United States.” This is not unlike many individuals around the world today; at least as of late – in the era of FATCA, who assert they are not a U.S. citizen because they “relinquish[ed] it by the performance of certain expatriating acts with the required “intent” to give up the US citizenship” and did not notify the U.S. federal government.

The Court nevertheless found Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle retroactively subject to U.S. income taxation on her non-U.S. source income (up until she received a certificate of loss of nationality from the Department of State); for specific years even when the immigration law provisions of the day said she was no longer a U.S. citizen during that same retroactive period.

There have been many contemporary commentators who argue an individual does not need to (i) have, (ii) do, or (iii) receive any of the following, and yet still should be able to successfully argue they have shed themselves of U.S. citizenship and hence the obligations of U.S. taxation and reporting on their worldwide income and global assets –

(i) receive a U.S. federal government issued document (e.g., a certificate of loss of nationality “CLN” per 877A(g)(4)(C)),

(ii) receive a cancelation of a naturalized citizen’s certificate of naturalization by a U.S. court (per 877A(g)(4)(D)),

(iii) provide a signed statement of voluntary relinquishment from the individual to the U.S. Department of State (per 877A(g)(4)(B)), or

(iv) provide proof of an in person renunciation before a diplomatic or consular officer of the U.S. (per paragraph (5) of section 349(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1481(a)(5)), in accordance with 877A(g)(4)(C)).

Some older tax cases that interpreted similar concepts are worthy of consideration. They will certainly be in any brief of the attorneys for the U.S. Department of Justice, Tax Division and/or Chief Counsel lawyers for the IRS in any case where the individual challenges that none of the above items are required in their particular case to avoid U.S. taxation and reporting requirements.

The D’Hotelle case is illustrative of the efforts taken by the Department of Justice, Tax Division in collecting U.S. income tax on a naturalized citizen. You will notice they did not take a sympathetic approach to her case. Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle was born in France in 1909 and died in 1968 in France, yet the U.S. government continued to pursue collection of U.S. income taxation on her foreign source income from the Dominican Republic, France and apparently Puerto Rico even after her death during a period of time when she used a U.S. passport. Lucienne D’Hotelle de Benitez Rexach, 558 F.2d 37 (1st Cir.1977). She, not unlike many individuals today, claimed she was not a U.S. citizen – or at least stated “I have never considered myself to be a citizen of the United States.”

Some of the particularly interesting facts relevant to Ms. D’Hotelle, a naturalized citizen, which are relevant to the question of U.S. taxation of citizens, were set forth in the appellate court’s decision as follows:

Lucienne D’Hotelle was born in France in 1909. She became Lucienne D’Hotelle de Benitez Rexach upon her marriage to Felix in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1928. She was naturalized as a United States citizen on December 7, 1942. The couple spent some time in the Dominican Republic, where Felix engaged in harbor construction projects. Lucienne established a residence in her native France on November 10, 1946 and remained a resident until May 20, 1952. During that time s 404(b) of the Nationality Act of 19402 provided that naturalized citizens who returned to their country of birth and resided there for three years lost their American citizenship. On November 10, 1947, after Lucienne had been in France for one year, the American Embassy in Paris issued her a United States passport valid through November 9, 1949. Soon after its expiration Lucienne applied in Puerto Rico for a renewal. By this time she had resided in France for three years.

* * *

On May 20, 1952, the Vice-Consul there signed a Certificate of Loss of Nationality, citing Lucienne’s continuous residence in France as having automatically divested her of citizenship under s 404(b). Her passport . . . was confiscated, cancelled and never returned to her. The State Department approved the certificate on December 23, 1952. Lucienne made no attempt to regain her American citizenship; neither did she affirmatively renounce it.

* * *

Predictably, the United States eventually sought to tax Lucienne for her half of that income. Whether by accident or design, the government’s efforts began in earnest shortly after the Supreme Court invalidated *40 the successor statute4 to s 404(b). In in Schneider v. Rusk, 377 U.S. 163 (1964), the Court held that the distinction drawn by the statute between naturalized and native-born Americans was so discriminatory as to violate due process. In January 1965, about two months after this suit was filed, the State Department notified Lucienne by letter that her expatriation was void under Schneider and that the State Department considered her a citizen. Lucienne replied that she had accepted her denaturalization without protest and had thereafter considered herself not to be an American citizen.

There are other facts that make clear the government was not fond of her husband, the income that he earned and how he managed his and his wife’s assets during and after her death. The Court also discusses at length the fact that she had used a U.S. passport during the years when she alleges she was not a U.S. citizen. The Court goes on to analyze her U.S. citizenship, and the following discussions are illustrative of the ultimate tax consequences.

The government contends that Lucienne was still an American citizen from her third anniversary as a French resident until the day the Certificate of Loss of Nationality was issued in Nice. This case presents a curious situation, since usually it is the individual who claims citizenship and the government which denies it. But pocketbook considerations occasionally reverse the roles. United States v. Matheson, 532 F.2d 809 (2nd Cir.), cert. denied 429 U.S. 823, 97 S.Ct. 75, 50 L.Ed.2d 85 (1976). The government’s position is that under either Schneider v. Rusk, supra, or Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253, 87 S.Ct. 1660, 18 L.Ed.2d 757 (1967), the statute by which Lucienne was denaturalized is unconstitutional and its prior effects should be wiped out. Afroyim held that Congress lacks the power to strip persons of citizenship merely *41 because they have voted in a foreign election. The cornerstone of the decision is the proposition that intent to relinquish citizenship is a prerequisite to expatriation.

411 F.Supp. at 1293. However, the district court went too far in viewing the equities as between Lucienne and the government in strict isolation from broad policy considerations which argue for a generally retrospective application of Afroyim and Schneider to the entire class of persons invalidly expatriated. Cf. Linkletter v. Walker, supra. The rights stemming from American citizenship are so important that, absent special circumstances, they must be recognized even for years past. Unless held to have been citizens without interruption, persons wrongfully expatriated as well as their offspring might be permanently and unreasonably barred from important benefits.6 Application of Afroyim or Schneider is generally appropriate.* * *

During the interval from late 1949 to mid-1952, Lucienne was unaware that she had been automatically denaturalized.

* * *

Part I: New TIGTA Report to Congress (Sept 30) Has International Emphasis on Collecting Taxes Owed by “International Taxpayers”: Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA)

TIGTA’s Semiannual Reports – Today’s Report with International Considerations – Part I

The Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Department of Justice (Tax Division) are the “soldiers” on the ground used to enforce U.S. federal tax law. They interpret the law, in no small part based upon the expertise and input of the myriad of experts in the U.S. Treasury, IRS and DOJ.

However, there are outside forces which oftentimes seem to have an “over-sized” influence on how, when and what priorities are identified in the IRS and DOJ. One of those powers of course is the Administration which makes up the Treasury Department and the very Department of Justice. The green book proposals of the Treasury and different policy proposals are an example. The other organization, within the Executive Branch is the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA).

TIGTA is the sort of “watch dog” over the IRS that independently reviews the work undertaken and often times questions that work and the IRS’ efforts. Per its own website it describes itself as:

The Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) was established in January 1999 in accordance with the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 (RRA 98) to provide independent oversight of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) activities. As mandated by RRA 98, TIGTA assumed most of the responsibilities of the IRS’ former Inspection Service.

TIGTA is separate and apart from the Taxpayer Advocate Service (“TAS”). See, excerpts of TAS reports here.

Another important influence is the Congress. See a prior post from September 2014 on this topic: How Congressional Hearings (Particularly In the Senate) Drive IRS and Justice Department Behavior

Part II: U.S. Department of State has Allowed (Starting in at least 2013) USCs to Keep their U.S. Passports After Oath and Prior to Receiving CLN

See the first post on this topic: U.S. Department of State has Allowed (Starting in at least 2013) USCs to Keep their U.S. Passports After Oath and Prior to Receiving CLN, Posted on March 17, 2015

A U.S. citizen is required to have a U.S. passport to enter the U.S., according to the immigration law regulations 22 CFR § 53.1 require that a U.S. citizen have a U.S. passport to enter or depart the United States.  The relevant part of the regulations is § 53.1(a) which provides as follows:

The relevant part of the regulations is § 53.1(a) which provides as follows:

Passport requirement; definitions.

The U.S. Department of State does not always provide any specific document, e.g., a certified copy of any of the following documents, after you take the oath of renunciation:

Form DS-4080, Oath of Renunciation of the Nationality of the United States.

Not having a U.S. passport can of course be problematic if the individual needs to travel in or out of the U.S. for a period of time after taking the oath, but before receiving the CLN. See, The Importance of a Certificate of Loss of Nationality (“CLN”) and FATCA – Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, Posted on June 1, 2014

Fortunately, I have been told by several Chiefs of American Citizen Services in different U.S. Consulates and U.S. Embassies that they have been advised from Washington that they are NOT required to physically take the U.S. passport, until after the issuance of the CLN. This now seems to be consistent practice throughout the world, and most all Chiefs of American Citizen Services use this approach, based upon my personal experience with different clients.

Timing Issues for Lawful Permanent Residents (“LPR”) Who Never “Formally Abandoned” Their Green Card

The “tax expatriation” statutory provisions are fraught with ambiguity and incomplete answers for those individuals who have cases that span different time periods. This is because the law has been changed numerous times over the last several years and ad hoc concepts added, including the technical concept of “long-term residents” for the first time in 1996. As has been previously explained, the first “expatriation tax” law was not adopted until 1966 as part of the The Foreign Investors Tax Act of 1966 (“FITA”) – The Origin of U.S. Tax Expatriation Law (Posted on April 6, 2014).

Next, 1996 amendments kept the basic regime but added a number of key concepts, including “long-term residents”. The changes in the law in 2004 made significant changes and in 2008 the first “mark to market” regime was adopted. Each time, the concept of “long-term residents” was maintained, but without clear thought as to the meaning and timing of “expatriation” in various cases. See, Timeline Summary of Changes in Tax Expatriation Provisions Since 1996, (Posted on April 9, 2014)

Unfortunately, none of these amendments to the law over the years carefully incorporated transition and timing rules for cases where the individual has lived in (or had U.S. citizenship or LPR) during one more of these time periods:

- 1966-1996

- 1996-2004

- 2004-2008

- 2008-present

There are many inconsistent concepts among the law and one clear example is demonstrated by an individual who became a lawful permanent resident prior to 1996 and prior to amendments in the definition of a “resident alien” which was adopted generally in the federal tax in the law in 1984. This 1984 definition was not part of any specific “expatriation tax” provisions.

Remember, the technical definition of who is a “resident alien” is the basic definition of who is generally subject to U.S. income taxation on their worldwide income. See, Co-author. “Tax Simplification: The Need for Consistent Tax Treatment of All Individuals (Citizens, Lawful Permanent Residents and Non-Citizens Regardless of Immigration Status) Residing Overseas, Including the Repeal of U.S. Citizenship Based Taxation,” by Patrick W. Martin and Professor Reuven Avi-Yonah, September 2013.

Prior to 1984, a LPR was not necessarily an income tax resident of the U.S. This concept of LPR (i.e., a “green card”) driving U.S. income tax residency was adopted in 1984, long before Congress became obsessed with U.S. individual tax expatriation. For background in the law, see the 1985 Penn State Law Review Article – Internal Revenue Code 7701(b): A More Certain Definition of Resident

The Joint Committee on Taxation report on the 1984 changes in the tax law (“General explanation of the revenue provisions of the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 : (H.R. 4170, 98th Congress; Public Law 98-369)“) addressing the tax residency test of “lawful permanent residency” rules provides the following language:

. . . The Act defines “lawful permanent resident” to mean an individual who has the status of having been lawfully accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States as an immigrant in accordance with the immigration laws, if such status has not been revoked or administratively or judicially determined to have been abandoned. Therefore, an alien who comes to the United States so infrequently that, on scrutiny, he or she is no longer legally entitled to permanent resident status, but who has not officially lost or abandoned that status, will be a resident for tax purposes. The purpose for this requirement of revocation or determination is to prevent aliens from attempting to retain an apparent right to enter or remain in the United States while attempting to avoid the tax responsibility that accompanies that right.

The logic of the LPR test is clear based upon this explanation. If one has the right to live in the U.S., they cannot avoid the tax responsibility that accompanies that right. However, as immigration lawyers will explain, there is no right to enter the U.S. after you have abandoned your LPR status and moved outside the U.S. on a permanent basis.

At the same time, there is other discussion in the report that would support the position that these provisions only apply for the years 1985 and thereafter (long after many individuals obtained LPR status, but who moved out of the country – e.g., in cases where individuals obtained LPR in the 1970s and left before 1985). Specifically, the explanation in the Joint Committee of Taxation is as follows:

. . . The purpose of this effective date rule is to delay tax resident status for only new green cardholders for a short time. Congress understood further that an alien may acquire lawful permanent resident status for immigration purposes before U.S. presence. Congress sought to impose tax resident status on all lawful permanent residents once they arrive in the United States. The Act does not affect the determination of residence, even for green card holders, for taxable years beginning before January 1, 1985.

Of course, the report by the Joint Committee on Taxation (“JCT”) is not the law and does not bind the IRS or the taxpayer. However, the JCT usually get their explanations of the law right.

Why is all of this important for LPRs who never formally abandoned their “green card”? The IRS might well try to argue they never terminated their U.S. federal income tax residency for purposes of the “tax expatriation provisions”, as later versions of the statute impose an obligation to notify the IRS. If the individual never notified the IRS, the government might ar

See, for instance Section 7701(b)(6) with specific rules for LPR individuals who live in a country with a U.S. income tax treaty. Importantly, the definition of a lawful permanent resident for tax purposes (as defined in Section 7701(b) ) is not identical to the definition for immigration law purposes as the legislative history to the 1984 amendments to the law explains.

See, Oops…Did I “Expatriate” and Never Know It: Lawful Permanent Residents Beware! International Tax Journal, CCH Wolters Kluwer, Jan.-Feb. 2014, Vol. 40 Issue 1, p9.

Finally, the information required as part of the process of formal abandonment is much more extensive than in the past.

A prior post discussed the published USCIS immigration form I-407 for LPRs who must now use it when formally abandoning LPR status. See, More Information and More Information: USCIS Creates New Form for Abandonment of Lawful Permanent Residency

See, new I-407 Form requires that much more information and is 2 pages in length.

Coming Back to the U.S. as a Permanent Resident (“Repatriating”)?

As discussed in the last post, this post addresses immigration law exclusively by a guest post writer, Ms. Teodora Purcell. She provides a good overview of EB-5 visas and the current law and likely changes in the near future.

***************************

The Pros and Cons of the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program

The EB-5 Immigrant Investor program was created by the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”) of 1990 to stimulate the US economy through capital investments made by foreign investors to create jobs. It attracts capital by facilitating US permanent resident status (aka “green card”) for foreigners who make a $1 million USD (or in some cases, $500,000 USD) investment in an eligible business that results in at least ten US jobs and benefits the US economy.[1]

The pros of the EB-5 program to the US are evident from the numbers. In FY 2014, 10,928 EB-5 petitions were filed with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”), 5,115 approved, and 12,453 pending, which translates into over $2.5 billion approved for investment and an additional $6.2 billion in capital awaiting federal adjudication, and the creation of thousands of US jobs.[2] EB-5 capital is also an attractive low cost funding tool for project developers in the US, while it offers the foreign investor a path to permanent residency that is not visa backlogged and does not require sponsorship by a US employer or relative. But is the EB-5 an easy and quick way “to purchase your green card”?

Basic EB-5 Requirements

The EB-5 program includes two separate avenues: (1) Direct EB-5 investment – where the investor invests in an enterprise and plays a role in management or policy making, which will directly create ten jobs, or (2) Regional Center based EB-5 investment – where the investor invests in a USCIS approved regional center and plays a more passive role by having policy making authority. Both require: (1) the investment to be made in a for-profit, new commercial enterprise;[3] (2) a contribution of capital at risk in the amount of $1,000,000 USD, or $500,000 USD[4] if the business is in a targeted employment area (i.e. high unemployment or rural area), aka “TEA”;[5] (3) the investment to be used for creation of at least ten full time jobs for US workers;[6] and (4) the investor to establish the path and the lawful source of the investment.

Pros and Cons of Direct and Regional Center EB-5 Investments

The Regional Center (“RC”) is an entity designated and regulated by USCIS, which pools EB-5 capital from multiple foreign investors in job-creating economic development projects within a defined geographic region and designated industries.[7] USCIS has approved approximately 600 RCs[8] and 95% of the EB-5 petitions are based on a RC investment. Notably, EB-5 RC investment funds are subject to U.S. securities and anti-fraud laws and regulations,[9] and the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) and USCIS are raising awareness of how the EB-5 program can be misused and of the importance of proper due diligence to be conducted by foreign investors.[10]

The direct EB-5 program is permanent, whereas the RC EB-5 program sunsets on September 30, 2015, but is expected to be reauthorized by Congress for another five years, and there is proposed legislation to make it permanent.[11] The most recent bipartisan bill on the RC EB-5 program, The American Job Creation and Investment Promotion Reform Act, was introduced on June 3, 2015, known as The Leahy-Grassley Bill.[12] The proposed legislation would reauthorize the EB-5 RC program until September 30, 2020, rather than make it permanent, and will provide an overhaul of reforms to improve the program’s integrity, including raise the requirement investment amount to $800,000/ $1,200,000, respectfully.[13]

With the direct EB-5 investment, the foreign national accomplishes not only an immigration purpose but also a purpose of investing in a business that he or she runs and that may provide significant return, whereas with the RC EB-5 investment, the rate of return is typically 0.5-2% and the investor plays a more passive role. However, the direct EB-5 investor must prove direct employment of ten U.S. workers, whereas, with RC EB-5 investment, the job creation is shown by a combination of direct, indirect and induced employment using reasonable economic methodologies. Most (but not all) RCs are located in $500,000 TEAs but there can be direct EB-5 investments that also qualify for the reduced capital. Both EB-5 options require the investor to be engaged in the “management” of the enterprise, which can be satisfied if the investor is a limited partner with the rights, powers and duties normally granted to limited partners under the Uniform Limited Partnership Act.[14] Which EB-5 option to choose requires an individualized analysis of the investor’s circumstances and goals.

No Fast Track EB-5 Process and No Guaranteed US Permanent Residence

The EB-5 investors are not guaranteed a green card because of the lengthy process and possibility that the project in which they invest could fail or undergo material changes, and there is no expedite processing of EB-5 petitions. The process starts with the filing of an I-526 immigrant entrepreneur petition with USCIS, in which the investor must establish the lawful source of funds, document the path of the required investment, and show that the ten US jobs will be created within two years,[15] or that the jobs have already been created as a result of the investment.

The filing of an I-526 petition alone does not give the investor the right to stay or work in the US. Current I-526 average processing time is approximately 14 months and the I-526 approval does not give the investor permanent residence. Rather, after the approval, if the investor is outside the US, he or she and dependent family members will apply for their immigrant visas at the US Consulate in their home country, which requires additional documentation, security checks and adds another 6-12 months to the process. If the investor is in the US in valid nonimmigrant status, he or she will adjust status to permanent resident in the US, which takes about six months.[16] So after 2-3 years (provided no visa retrogression), the investor receives a green card that is conditional and valid for only two years.

Within 90 days of the conditional green card expiration (i.e. between the 21 to 24 month after the green card approval), the investor must file an I-829 application to remove the condition on permanent residence with USCIS[17], and prove that the investment has been sustained and that the requisite jobs have been created or will be created within a “reasonable time.”[18] The current average I-829 processing time is 10 months and if unsuccessful, the EB-5 investor may not only lose the green card but end up in removal proceedings. If the I-829 is approved, the EB-5 investor receives his or her permanent green card. During this process, the EB-5 investment must remain in the enterprise until the condition is removed (i.e. for 4-5 years), whereas in all other employment based green card categories, the result is a permanent green card and no such significant financial commitment is required.

The EB-5 program accounts for less than 1% of the immigrant visas issued annually by the US and throughout the process, investors are subject to the same background checks as applicants in any other visa category, and their ability to eventually apply for citizenship is the same as others. The INA allocates 10,000 EB-5 immigrant visas, of which 3,000 are reserved for the RC program, and no more than 7 percent of the visas can be allocated to any one country.[19] Since close to 85% of the investors are from China, for the first time in September 2014, the EB-5 visas became unavailable for Chinese nationals, and EB-5 visa backlog for Chinese investors may be expected in 2015. There are more significant immigrant visa quota backlogs in other categories of family and employment-based immigration, which is why the EB-5 still remains attractive.

EB-5 and Other Green Card Options

Despite the challenges investors may face in tracing the invested funds or in the job creation, and the possibility of visa backlog for some, the EB-5 is still a good option, although it is not the panacea for all foreign nationals seeking permanent residence in the US. There are other employment based visa options that may be available for the investor and these alternatives, if successful, lead to a permanent green card, do not require placement of a $1,000,000 investment at risk, and there are minimal concerns about visa availability. For the foreign nationals who choose the EB-5 green card avenue, it is important to put together a competent team that includes an immigration counsel, as well as business, tax, and securities counsels, to advise on the multiple complex issues that go into determining whether the EB5 green card path is the right choice for the client.

Immigrant investors and entrepreneurs bring substantial value to the United States, not only through the capital they deploy or the jobs they create, but also with the knowledge and experience they bring to US businesses, and working with such clients is very rewarding.

[1] The immigration EB-5 laws can be found at INA§203(b)(5); 8 CFR§204.6 and 8 CFR§216.6.

[2] https://iiusa.org/blog/government-affairs/uscis-government-affairs/citizenship-immigration-services-uscis-adjudication-data-i526-i829-petitions-reveal-unprecedented-growth-eb5-program-fiscal-year-2014/ /

[3] 8 CFR §§204.6(e) & (h).

[4] There is a proposed legislation to increase the investment amount to $1,200,000 USD and $800,000 USD, respectively. See S.1501, The American Job Creation and Investment Promotion Reform Act, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1501/text

[5] 8 CFR §§204.6(e) & (f)(2).

[6] 8 CFR §§204.6(e) & (j)(4). The USCIS deems the two year period to commence six months after the adjudication of the I-526 petition. See USCIS Policy Memorandum (May 30, 2013)

[7] 8 CFR §204.6(e).

[8] http://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/permanent-workers/employment-based-immigration-fifth-preference-eb-5/immigrant-investor-regional-centers

[9] The interest being offered and sold in an EB-5 offering by regional centers constitute securities. See Securities Act of 1933; Securities Exchange Act of 1934.).

[10] For more information, see http://www.sec.gov/investor/alerts/ia_immigrant.htm

[11] S.744, H.R. 2131, H.$. 4178, and H.R. 4659 in the 113th Congress

[12] S.1501, The American Job Creation and Investment Promotion Reform Act, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1501/text. Also see http://www.leahy.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/The%20American%20Job%20Creation%20and%20Investment%20Promotion%20Reform%20Act.pdf

[13]If implemented, the Leahy-Grassley legislation will have a significant impact on Regional Centers and investors alike, some of the most notable changes proposed to the EB-5 Program include: (1) Raise the minimum investment amount for all EB-5 investors to $800,000 for TEAs and $1,200,000, respectively; (2) Establish an “EB-5 Integrity Fund” to cover the costs associated with audits and site visits to detect fraud in the United States and abroad; (3) Increased oversight of TEA designation; (4) Expanded USCIS authority to terminate Regional Center designation; (5) Establish a premium processing option to expedite USCIS adjudication of EB-5 petitions at an additional filing fee.

[14] 8 CFR §204.6(j)(5).

[15] The USCIS requires that the I-526 petition be accompanied by a detailed and credible business plan compliant with the requirements in the precedent decision of Matter of Ho, 22 I&N Dec. 206 (INS Assoc. Comm’r, Examinations, 1998).

[16] https://egov.uscis.gov/cris/processingTimesDisplay.do;jsessionid=dbcqHwZ-eEZPOcoHaz5Ru.

[17] 8 CFR §216.6

[18] 8 CFR §216.6(a)(4)(iv) . In its May 30, 2013 Policy Memorandum, USCIS has interpreted “reasonable time” to mean one year, starting at the end of the conditional residence period.

[19] INA §203(a) ; INA §204(1) & INA§202(a)(2).

Teodora Purcell | Attorney at Law

FRAGOMAN

11238 El Camino Real, Suite 100, San Diego, CA 92130, USA

Direct: +1 (858) 793-1600 ext. 52424 | Fax: +1 (858) 793-1600

TPurcell@Fragomen.com

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 6

- Next →