Criminal Tax Considerations

W-8s for U.S. Citizens Abroad: Filing False Information with Non-U.S. Banks

Individuals who do not specialize in U.S. federal tax law, often have little detailed understanding of the U.S. federal “Chapter 3” (long-standing law regarding withholding taxes on non-resident aliens and foreign corporations and foreign trusts) and “Chapter 4” (the relatively new withholding tax regime known as the “Foreign Account Tax  Compliance Act”) rules.

Compliance Act”) rules.

Indeed, plenty of U.S. tax law professionals (CPAs, tax attorneys and enrolled agents) do not understand well the interplay between these two different withholding regimes –

- 26 U.S. Code Chapter 3 – WITHHOLDING OF TAX ON NONRESIDENT ALIENS AND FOREIGN CORPORATIONS

- 26 U.S. Code Chapter 4 – TAXES TO ENFORCE REPORTING ON CERTAIN FOREIGN ACCOUNTS

Plus, the IRS forms have been significantly modified over the years; with increasing factual representations that must be made by individuals who sign the forms under penalty of perjury. They are complex and not well understood. For instance, the older 2006 IRS Form W-8BEN for companies was one page in length and required relatively little information be provided.

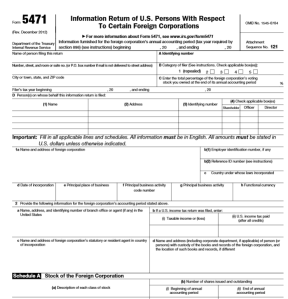

The entire form is reproduced here; indicating how foreign taxpayer information was optional and generally there was no requirement to obtain a U.S. taxpayer identification number. It was governed exclusively by Chapter 3 and the regulations that had been  extensively produced back in the early 2000s.

extensively produced back in the early 2000s.

The forms were even easier before those regulations (see old IRS Form 1001). No taxpayer identification numbers were ever required and virtually no supporting information regarding reduced tax treaty rates on U.S. sources of income.

Life was simple back then – compared to today!

The one thing all of these forms have in common is that all information was provided and certified under penalty of perjury. Current day IRS Forms W-8s can typically be completed accurately by experts who understand the complex web of rules. Plus, multiple versions of W-8s exist today; most running some 8+ pages in length.

See the potpourri of current day W-8 forms –

Making certifications under penalty of perjury are more complex, the more and more factual information that is being certified. If I certify the dog I see in front of me is “white and black” that is not a complex certification, if I see the dog and see the “white and black”. If the dog also has some brown coloring, my certification would necessarily not be false.

However, if I have to certify as to the colors of each dog in a pack of 8 dogs (and each and every color that each dog is/was), that becomes a much more complicated certification.

That’s my analogy for the old IRS Forms W-8s and the current day IRS Forms W-8s.

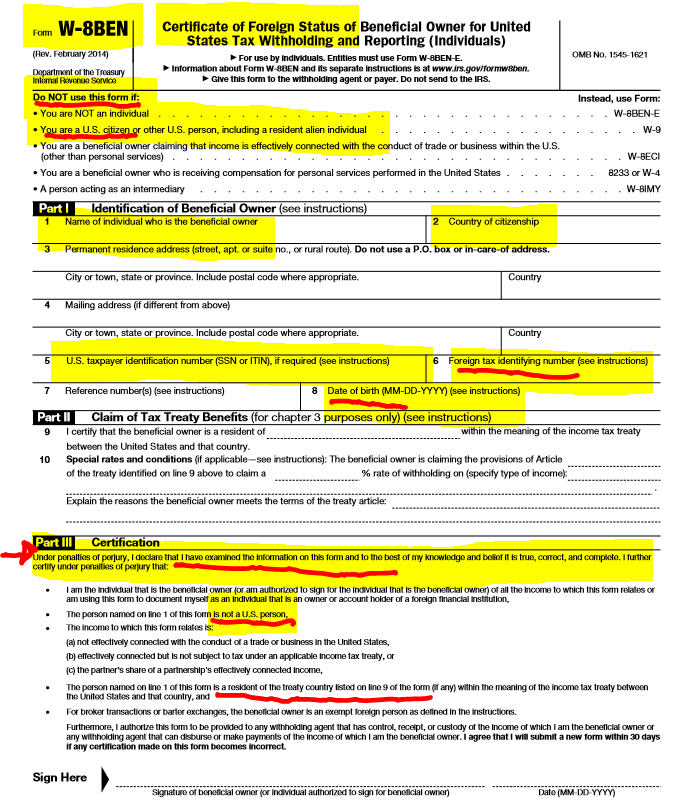

Compare that form, of just 10 years ago, with what is required and must be certified to under current law. It can be daunting.

Now to the rub. Individuals who certify erroneously or falsely, can run a risk that the government asserts such signed certification was done intentionally. I have seen it happen in real cases; even though the individual layperson (particularly those who speak little to no English and live outside the U.S.) typically has little understanding of these rules. They typically sign the documents presented to them by the third party; usually the banks and other financial institutions.

The U.S. federal tax law has a specific crime, for making a false statement or signing a false tax return or other document – which is known as the perjury statute (IRC Section 7206(1)). This is a criminal statute, not civil. Some people are also under the misunderstanding that a false tax return needs to be filed. The statute is much broader and includes “. . . any statement . . . or other document . . . “.

(1) Declaration under penalties of perjury

Willfully makes and subscribes any return, statement, or other document, which contains or is verified by a written declaration that it is made under the penalties of perjury, and which he does not believe to be true and correct as to every material matter; or . . .

Therefore, if a U.S. citizen living overseas (or anywhere) signs IRS Form W-8BEN (or the bank’s substitute form, which requests the same basic information), that signature under penalty of perjury will necessarily be a false statement, as a matter of law. Why? By definition, the statute says a U.S. citizen is a “United States person” as that technical term is defined in IRC Section 7701(a)(30)(A). Accordingly, IRS Form W-8BEN, must only be signed by an individual who is NOT a “United States person”; who necessarily cannot be a United States citizen. To repeat, a United States citizen is included in the definition of a “United States person.” Plus, the form itself, as highlighted at the beginning of the form, warns against any U.S. citizen signing such form.

Accordingly, if a U.S. citizen were to sign IRS Form W-8BEN which I have seen banks erroneously request of their clients, they run the risk that the U.S. federal government will argue that such signatures and filing of false information with the bank was intentional and therefore criminal under IRC Section 7206(1). See a prior post, What could be the focal point of IRS Criminal Investigations of Former U.S. Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents?

Indeed, criminal cases are not simple, and I am not aware of any single criminal case that hinged exclusively on a false IRS Form W-8BEN. However, I have seen cases, where the government has alleged the U.S. born individual must have signed the form intentionally, knowing the information was false. It’s a question of proof and of course U.S. citizens wherever they reside, should take care to never sign an IRS Form W-8BEN as an individual certifying they are not a “United States person”; even if they think they are not a U.S. person

For further background information on this topic, see a prior post: FATCA Driven – New IRS Forms W-8BEN versus W-8BEN-E versus W-9 (etc. etc.) for USCs and LPRs Overseas – It’s All About Information and More Information

Part II: “Neither Confirm nor Deny the Existence of the TECs Database”: IRS Using the TECs Database to Track Taxpayers Movements – and Assets

Part II: This is a follow-up to the federal government’s database known as “TECS” (Treasury Enforcement Communication System)that is now operated by the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”). The IRS uses it to track travel, trips, movement and even asset movements (e.g., wire transfers) by U.S. citizen taxpayers; including those residing outside the U.S.

See, “Neither Confirm nor Deny the Existence of the TECs data”: IRS Using the TECs Database to Track Taxpayers Movements –, posted Dec. 13, 2014.

This previous post described how the U.S. federal government uses the TECS to locate assets and travel patterns of U.S. citizens; specifically outside the U.S. The IRS trains their employees to (1) Not discuss TECS with taxpayers; (2) Neither confirm nor deny existence of TECS; (3) Keep in separate “Confidential” envelope; and (4) Stamp documents as “OFFICIAL USE ONLY”

The image in this post reflects a page from IRS training materials for their employees; e.g., revenue agents (those individuals who audit taxpayers and determine tax deficiencies and the like), revenue officers (those individuals who work on collecting taxes owed or alleged to be owed) and chief counsel attorneys (those individuals who litigate tax cases against taxpayers); among other IRS employees.

Frankly, there is not a lot of detailed law about how and when the IRS can use TECS or other tracking techniques of individuals and their assets. There are no tax cases (at least none that I am aware of) where the Courts have tried to impose limits on the use and  methods of the federal government in collecting this type of TECS information. Indeed, there are specific provisions granting broad use of taxpayer information when the government alleges there is a “terrorist incident, threat, or activity” as that term is defined in IRC Section § 6103.

methods of the federal government in collecting this type of TECS information. Indeed, there are specific provisions granting broad use of taxpayer information when the government alleges there is a “terrorist incident, threat, or activity” as that term is defined in IRC Section § 6103.

On the other hand, there are important laws about how the IRS cannot generally disclose taxpayer information. For instance, see the same code section IRC Section § 6103 for wrongful disclosures of taxpayers’ information. That statute makes it a violation (even a criminal violation in certain willful circumstances) to disclose taxpayer information in “most” (or at least many) circumstances. The statute is comprehensive and there is a lot of case law interpreting various provisions. A good overview of the statute can be found in the Criminal Tax Manual for the Department of Justice, Tax Division – Chapter 42.00

A recent case (United States v. Garrity, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 66372 (D. Conn. 2016), discussed in Jack Townsend’s blog, was one where the IRS had disclosed the name of a deceased taxpayer Paul G. Garrity, Sr. regarding his foreign (non-U.S.) accounts. The disclosure included IRS investigation techniques that were disclosed as part of a FOIA request, which ultimately made it to the public. This was found to be disclosure of return information as defined by IRC Section § 6103. However, the Court there found that there was no violation of the statute by the IRS, as the taxpayer was deceased by the time the claim was brought by the estate. The government made a Title 31 FBAR penalty assessment of over US$1M including interest and penalties that is still pending.

It seems to me that the use of the TECS database by the IRS and Section 6103 are a bit like two heads of a coin. It all deals with taxpayer information and what rights, if any do taxpayers have to protect their personal and financial information – especially where it can (purposefully or inadvertently – e.g., through a data breach/hacking) be released to the public.

There are many unanswered questions as there has been little to no litigation regarding how and when the TECS database can and should be used.

Does the government have any limits on its use?

This ultimately becomes more of a policy discussion about how and to what extent can/should the federal government have and use and collect personal financial and travel information of individuals (particularly for tax purposes)?

As FATCA data collection has now allowed exchanges of millions of records, these questions in my view take on even greater importance. See 21 Dec 2015 post, Foreign Government Receives a “FATCA Christmas Gift” from IRS: 1 Gigabyte of U.S. Financial Information.

See a prior related post, 19 Jan 2014 – Should IRS use Department of Homeland Security to Track Taxpayers Overseas Re: Civil (not Criminal) Tax Matters? The IRS works with Department of Homeland Security with TECs Database to Track Movement of Taxpayers

Part II: U.S. Department of State Communications to USCs overseas Regarding Tax Obligations with IRS

A recent post discussed a rather surprising development of how the – U.S. Department of State, Starts Communicating with U.S. Citizens Overseas Regarding Tax Obligations with the IRS

There are several observations to be made about this approach.

First, some USCs living overseas will find this a welcome development, as it provides a method of  basic education of how U.S. tax laws work. The newer U.S. passports do have an obscure reference to U.S. tax obligations of USCs. In the past, there was generally no communications from the U.S. Department of State to USCs, including newly naturalized U.S. citizens about their U.S. tax obligations.

basic education of how U.S. tax laws work. The newer U.S. passports do have an obscure reference to U.S. tax obligations of USCs. In the past, there was generally no communications from the U.S. Department of State to USCs, including newly naturalized U.S. citizens about their U.S. tax obligations.

Second, there is much helpful information provided in the U.S. Department of State’s explanation. The key tax forms that are most relevant for USCs and LPRs residing overseas are explained in the government e-mail. See, USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S. – Key Tax and BSA Forms

All of the following forms are identified by the U.S. Department of State:

- Substantive Income Tax Forms (Affecting Tax Liability)

- Foreign Earned Income Exclusion – IRS Form 2555

- Foreign Tax Credits – IRS Form 1116

- Information Tax Forms (Not Affecting Tax Liability, but with Substantial Penalties for Failure to File)

- IRS Form 8938 Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets

- Foreign Bank Account Reports (“FBAR”) – FinCEN Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts through the BSA E-Filing System website.

These are the most relevant forms for the majority of USCs and LPRs; although there are numerous other forms and calculations that may be required depending upon the particular circumstances, income, assets, employment, etc. for each individual

The third observation, relates to how employees of the U.S. Department of State will use this information and communicate with USCs? Will they begin asking (even if infrequently) whether a U.S. citizen overseas is in compliance with their U.S. federal tax requirements? What are the consequences to the U.S. citizen if they state yes, no or refuse to answer? What can happen to an individual if they provide a false statement to a federal employee or file a false document? See What could be the focal point of IRS Criminal Investigations of Former U.S. Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents?

The fourth and last observation, is whether the IRS will begin providing USC taxpayer information on a regular basis to the U.S. Department of State? The law provides limitations upon how the IRS can disclose and provide taxpayer information. See, 26 U.S. Code § 6103 – Confidentiality and disclosure of returns and return information

However, there are significant exceptions in the law, that do allow disclosure of taxpayer financial and taxpayer information to other agencies (particularly “Intelligence Agencies,” which presumably includes the U.S. Department of State). See, for instance, IRC Section 6103(i)(7). The statutory requirements of 6103(i)(7) are not particularly rigid.

More on FATCA Driven IRS Forms, specifically including IRS Form W-8BEN-E ~ It’s All About Information and More Information

The lives of United States Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents living outside the U.S. has necessarily become more complicated due to FATCA.

Previous posts discussed unintended consequences of FATCA. See, Part 2 – Unintended Consequences of FATCA – for USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S.

Also, see, Part 1- Unintended Consequences of FATCA – for USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S.

– One of the most significant unintended consequence, is that the U.S. federal government (the IRS, the Treasury Department, or  Congress) never initially even contemplated USCs and LPRs living overseas. In other words, the group targeted were U.S. resident individuals who were evading taxes through foreign financial institutions. I say this, based upon extensive conversations I have had with ex-government officials and some government officials who were involved in the original policy discussions.

Congress) never initially even contemplated USCs and LPRs living overseas. In other words, the group targeted were U.S. resident individuals who were evading taxes through foreign financial institutions. I say this, based upon extensive conversations I have had with ex-government officials and some government officials who were involved in the original policy discussions.

Currently, the IRS has revised or created the following new tax forms as a result of FATCA (all in  the English language), which can be located at the IRS website at FATCA – Current Alerts and Other News:

the English language), which can be located at the IRS website at FATCA – Current Alerts and Other News:

Importantly, none of these forms are in other key languages such as Spanish, French, Mandarin, Cantonese, Portuguese, etc. Imagine the daunting nature of completing these complex forms just in English when English is your first language, let alone completing them when you speak little to no English.

As the financial and account information of U.S. citizens and LPRs at financial institutions worldwide is now being collected to be reported in 2015 to the IRS under FATCA, a better understanding of FATCA forms is required. A follow-up post will specifically discuss how financial and account information of non-U.S. shareholders and owners of foreign corporations, companies and foreign trusts will also  indirectly be reported to the IRS, when there is a “substantial U.S. owner.”

indirectly be reported to the IRS, when there is a “substantial U.S. owner.”

A detailed discussion of how and when this information will be released to the IRS will be explained in a follow-up discussion of a passive “non-financial foreign entity” (“NFFE”) which will typically be a foreign corporation (non-U.S.), companies and foreign trusts.

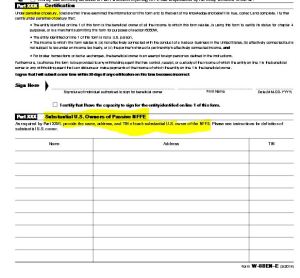

This information is set forth and requested in Parts XXX and XXIX on the last page of IRS Form W-8BEN-E on page 8. These items are highlighted here in yellow reflecting the information requested.

A follow-up post will explain what is a “passive” NFFE and what information is required to be reported per the form. For a better understanding of the importance of signing a document “under penalty of perjury” see Certifying Under Penalty of Perjury – Meeting the Requirements of Title 26 for Preceding 5 Taxable Years.

Part I: U.S. Citizens Residing Outside the U.S. Probably Have Some Solace Re: Acquittals of Swiss and Israel Bankers

U.S. taxpayers living outside the U.S. are increasingly becoming aware of the long arm of the U.S. tax law.

First, more and more individuals overseas are understanding the unique U.S. citizenship based taxation system. Unique in the world. See, Will Congress Intervene to make USC based Tax Laws More User Friendly to USCs and LPRs Residing Outside the U.S.?

Second, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (“FATCA”) and its breathtaking reach and scope, is also creating greater awareness of the costs and consequences to U.S. citizens overseas. See, Part 1- Unintended Consequences of FATCA – for USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S.

Third, U.S. federal government has become increasingly more aggressive with U.S. taxpayers and their worldwide assets more generally. See, FBAR Penalties for USCs and LPRs Residing Overseas – Can the Taxpayer have no knowledge of the law and still be liable for the willfulness penalty? See government memorandum.

Previous posts here have questioned how aggressive will the IRS and the Justice Department be against U.S. citizens residing oversees. See, Will the IRS treat a USC or LPR residing outside the U.S. who purposefully refuses to file U.S. income tax returns and information returns the same as “tax protesters”?

There are limits the government has, both practically and legally, in enforcing U.S. law overseas. See, U.S. Enforcement/Collection of Taxes Overseas against USCs and LPRs – Legal Limitations

A most significant limitation for the government reared its head twice in the last few hours, after two juries came back with acquittals of two separate bankers who were accused of aiding and abetting U.S. taxpayers. They were both employed by non-U.S. banks.

The most reverberating acquittal was the former head of wealth management at the large Swiss Bank UBS, Raoul Weil. He was indicted in 2008 and was a fugitive until his arrest in 2013 in Italy. The U.S. federal government had alleged he had aided and abetted U.S. taxpayers’ evade the reporting of billions of dollars of U.S. assets. According the Financial Times, the Florida jury only deliberated a little more than an hour on Monday 3 Nov. 2014, Ex-UBS banker cleared on US tax charges

Also, on Friday a federal jury in California deliberated and acquitted a former retired banker from the Israeli bank Mizrahi on conspiracy and other related tax crime charges. See Bloomberg, Ex-Mizrahi Octogenarian Banker Acquitted at Tax Trial.

These are both major setbacks for the government. The Department of Justice had previously released scathing press releases with the indictments, specifically including the indictment of Mr. Raoul Weil of UBS. These following statements were included:

“Professionals, including bankers, who promote fraudulent offshore tax schemes against the United States, will be held accountable,” said John A. Marrella, Deputy Assistant Attorney General of the Justice Department’s Tax Division. “These individuals face severe consequences including imprisonment and substantial fines.”

“The IRS is aggressively pursuing anyone who helps wealthy individuals hide their assets offshore and dodge the tax system,” said IRS Commissioner Doug Shulman. “As the global commerce and capital flows continue to increase, we have stepped up our efforts on international tax evasion.”

In these two cases, the juries obviously did not agree with the government that the bankers were illegally assisting their clients under U.S. law.

Part II of this post will discuss the impact these acquittals will likely have as the government attempts to pursue U.S. citizens on tax charges who live overseas.