citizenship taxation

Part I of Part II: The Gold Card – “It’s like the green card, but better and more sophisticated.”

Will the “gold card” sell to ultra high net worth investors around the world who want U.S. citizenship (“USC”)? What are the tax costs of USC? * About the Author: Patrick W. Martin

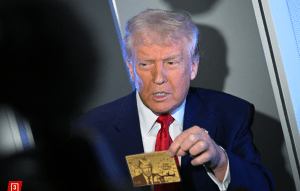

President Trump again announced on April 3, aboard Air Force One his plan:

See, the New York Post – Trump unveils $5 million ‘gold card’ for rich migrants emblazoned with his image

Whether the U.S. adopts a new “Gold Card” “For $5 million [that] we will allow the most successful job-creating people from all over the world to buy a path to U.S. citizenship,” is up to the U.S. government.

* Congressional Powers: Article I, Section 1, and Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution.

Congress can amend Title 8 and include a new “Gold Card” option.

Current law provides the EB-5 visa as one path towards a “green card” that ultimately can lead to U.S. citizenship through naturalization.

President Trump presented at his March 4th speech to a joint session of Congress, explaining the concept: “It’s like the green card, but better and more sophisticated. And these people will have to pay tax in our country.”

* Reducing the Deficit: $1.31 trillion more than Gov’t has collected in fiscal year (FY) 2025

Sounds like a panacea to help the U.S. federal deficit problem? If 100,000 of these “Gold Cards” were sold for $5M each, and these funds were paid directly over to the federal government, that would raise $500 billion dollars. If 1 million were sold, that would be $5 trillion dollars to use to pay down the deficit (running annually at far greater than $1 trillion dollars since 2019).

To put that into perspective, the EB-5 visa that also leads to a “green card” that can further lead to U.S. citizenship through naturalization has an annual visa limit of about 10,000. See, USCIS’s article – (16 Aug 2024) – Annual Limit Reached in the EB-5 Unreserved Category There have been multiple years where the annual visa limit was not met. Prior to 2015, the 10,000 visa limit was never met and in several years there were less than 500 EB-5 visas issued annually.

- EB-5 visa – Leading to a Green Card

There have been less than 150,000 EB-5 visas issued over the last 35 years since its adoption in 1990. Is it realistic to be able to “sell” even ten thousand $5M gold visas annually, when the “green EB-5 visa” costs $800,000 and has had less than 150,000 issued in nearly 35 years?

Plus, see the U.S. Department of State’s Immigrant Visa Statistics, including the – Annual Numerical Limits for Fiscal Year 2025 for more details about the EB-5 visa program statistics.

-

- Equity Investment for EB-5 visa – $800,000 (Does NOT go to the Government)

The total required equity investment amount for an EB-5 visa in the qualifying project, is only $800,000 (if in a “TEA”). See, EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program, as published by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). See, USCIS’s Chapter 2 – Immigrant Petition Eligibility Requirements. It used to be only $500,000 (1/10th of $5M). A TEA is a targeted employment area (“TEA”) that meets specific requirements under the law. If the capital investment is not in a TEA, the required minimal capital investment amount is $1,050,000 that increases in January 1, 2027 and each 5 years thereafter. Still about 1/5th the cost of a “gold visa”.

- U.S. Estate and Gift Tax Consequences for U.S. Citizens and those with a Green Card (“Gold Card”?)

Finally, maybe the biggest impact on who wants an investor visa that leads to U.S. citizenship depends largely upon the U.S. income tax and U.S. estate and gift tax consequences. There are many tax implications. See, my case Aroeste v United States – Order Nov 2023, that was appealed to the 9th Circuit by the Office of Solicitor General (DOJ). U.S. District Court ruled in favor of green card holder.

Ultra high net worth individuals around the world want to know the tax costs of U.S. citizenship. Importantly, new regulations were issued in January 2025 regarding the tax consequences of  renouncing USC and triggering the U.S. “expatriation tax” that is the primary focus of these materials. See, these regulations – here: Guidance Under Section 2801 Regarding the Imposition of Tax on Certain Gifts and Bequests From Covered Expatriates

renouncing USC and triggering the U.S. “expatriation tax” that is the primary focus of these materials. See, these regulations – here: Guidance Under Section 2801 Regarding the Imposition of Tax on Certain Gifts and Bequests From Covered Expatriates

These tax consequences of the “gold visa” will be explored in more detail in Part II.

For a more detailed discussion of tax issues tied to pre-immigration to the U.S., see my chapter of the tax implications of immigration to the U.S. (as opposed to emigration from it). I wrote the tax chapter in the latest edition of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (“AILA’s) – Immigration Options for Investors & Entrepreneurs (out of print) titled Key U.S. Tax Considerations for Investor Visa Applicants by Patrick W. Martin.

Another Common Misunderstanding of U.S. Tax Laws (Myth No. #8)

Myth #8: As a U.S. citizen (USC) there is no need to pay tax on income or gains from assets outside the U.S., as long as the proceeds are not repatriated to a U.S. bank or financial institution.

As a follow-on to the post of Nov. 19, 2015, See WSJ = World/Expats – For an Excellent Overview of U.S. Taxation for U.S. Citizen Individuals in Plain English, I just heard this one this past week from  a cross border businessman. It has a perfect logic to it the same as the idea that a controlled foreign corporation that moves cash to its own U.S. bank account (as opposed to a financial account outside the U.S.), is subject to U.S. income taxation at that moment.

a cross border businessman. It has a perfect logic to it the same as the idea that a controlled foreign corporation that moves cash to its own U.S. bank account (as opposed to a financial account outside the U.S.), is subject to U.S. income taxation at that moment.

Laypeople often focus on – “where is the money” not “who has *’recognized’ the income” irregardless of where the money or property is physically located.

This international business operator is thoughtful and has been doing cross border business for some 20+ years with a principle part of his business outside the U.S.; although he is a dual national citizen and hence necessarily a U.S. income tax resident.

It’s a fairly common misunderstanding that I have seen multiple times in my career.

The federal tax law does not look to where the property or income is physically located or earned; unlike some countries which have a territorial based taxation system for individuals, e.g., Costa Rica, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Panama, Singapore and Paraguay, among many others which are smaller economies.

Plus, the federal tax law is not changed by the laws of the country where the income was earned.

Instead, the tax law looks to who “recognized”* the income, irrespective of where the property or cash from that income is located.

A common sense example brings home the concept. Assume you live in Georgia (the one next to Florida not Russia) and sell real estate in Texas and leave the proceeds from the sale in a Texas bank. Texas may not impose individual income taxation on the sale of the Texas real estate (where the property was physically located), but still the state of Georgia looks to who earned the income. In this case, the income was earned by a resident of Georgia, so Georgia imposes taxation on the income from the sale, even though the cash proceeds from the sale are left in a Texas bank.

By analogy, this is how the U.S. federal government imposes taxation; with one important break in the analogy. The U.S. federal government treats USCs as income tax residents, irrespective as to where they reside; whereas George only taxes those who are physically resident in their state on a worldwide basis.

For instance, a U.S. citizen residing in Singapore, who sells real estate in a country outside both the U.S. and even Singapore, e.g., Malaysia where the tax rate on the real estate capital gains is 0%, will have earned that income in Malaysia (the where). Even if the U.S. citizen keeps his funds in a Malaysian bank or even moves the funds to a Singapore bank the country of residence (still the where), he or she will be subject to U.S. income taxation, since the USC status (the who) creates tax residency irregardless of the physical residency. See, Supreme Court’s Decision in Cook vs. Tait and Notification Requirement of Section 7701(a)(50) posted June 27, 2014 and The U.S. Civil War is the Origin of U.S. Citizenship Based Taxation on Worldwide Income for Persons Living Outside the U.S. ***Does it still make sense? posted April 1, 2014.

It does not matter that the funds are not moved to a U.S. bank account, just like it did not matter for the Georgian resident that she kept her proceeds from the Texas real estate sale’s transaction in a Texas bank.

- * The term “recognized” is a technical U.S. federal tax term that determines at that moment in time a U.S. taxpayer has income for federal tax purposes; and hence, generally the requirement to report the income on their tax return.

WSJ Asks the Question: Is the IRS Undercounting Americans Renouncing U.S. Citizenship?

Is the IRS Undercounting Americans Renouncing U.S. Citizenship?, posted Sept. 16, 2015.

The names of U.S. citizens who have renounced is published quarterly pursuant to IRC Section  6039G. See, prior related posts: 1,426 Individuals Give Up Passport: Record Number of U.S. Citizens Renouncing: Quarter 3 for 2015, October 30, 2015.

6039G. See, prior related posts: 1,426 Individuals Give Up Passport: Record Number of U.S. Citizens Renouncing: Quarter 3 for 2015, October 30, 2015.

No one knows for certain if the IRS (including the IRS per some of my conversations) is getting complete data from the Department of State regarding each name and individual.

The graph I have prepared shows the number of names reported quarterly as I track all reported names quarterly that related to clients and non-clients. The latest cumulative amounts for 2015 (which does not include the 4th quarter) shows 3,221 thus far in the year. If there is close to 1,400 as was the case for the last quarter, the total will be a record – by a bunch; i.e., close to 5,000 renunciations for the year.

Anecdotally, I have seen renunciations surge in our practice, largely as U.S. citizens residing around the world (typically in the “Accidental American” category) learn about the long arm of the U.S. tax law by way of their local financial institutions and reporting and documents requested as part of FATCA. See, Why Most U.S. Citizens Residing Overseas Haven’t a Clue about the Labyrinth of U.S. Taxation and Bank and Financial Reporting of Worldwide Income and Assets, posted Nov. 2, 2015.

None of this answers the question of whether there is under-reporting of the names? Indeed, the question will likely not be answered without more information provided by the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Treasury (i.e., the IRS officers responsible for issuing the names and report in the Federal Register).

The government is also likely to reject issuing information on these details to individuals and their advisers as part of a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request. I have had similar requests rejected by the government under the so called “Exemption 7(E)” of FOIA. See,

IT AIN’T FAIR: First (1) taxing me as a U.S. citizen and then (2) taxing me on my relinquishment or renunciation of U.S. citizenship or LPR abandoment and further (3) taxing my children on their inheritance from me!@!@!

This sums up the argument of many critics of U.S. citizenship based taxation of worldwide income.

Many may agree with this conclusion from an equity or sense of fairness argument. See proposal below at the end of this post.

However, the argument of fairness has little place in interpretations of Title 26, the U.S. federal tax law. For example, the U.S. Tax Courts are not courts of equity. See, The United States Tax Court – An Historical Analysis, Dubroff and Hellwig, footnote 668.

Also, virtually no courts of the U.S. find U.S. tax laws to be unconstitutional. It is a very rare occurrence that the U.S. Supreme Court even takes up a tax case to determine its constitutionality. The “Obamacare” with broad application throughout society was a case heard by the Supreme Court which upheld a law signed by President Obama on March 23, 2010, more correctly called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. That law increased Medicare taxes and imposed a penalty surcharge on individuals who do not maintain certain health coverage.

In contrast, U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents (LPRs) residing overseas are a relatively small population of the U.S. taxpayer population. Accordingly, it was only until late the U.S. government even began focusing on this population to collect taxes from them. See, Is the new government focus on U.S. citizens living outside the U.S. misguided or a glimpse at the new future?, posted March 6, 2014.

Finally, see various proposals to modify the law: e.g., U.S. Citizenship Based Taxation – Proposals for Reform – “Tax Simplification: The Need for Consistent Tax Treatment of All Individuals (Citizens, Lawful Permanent Residents and Non-Citizens Regardless of Immigration Status) Residing Overseas, Including the Repeal of U.S. Citizenship Based Taxation,” by Patrick W. Martin and Professor Reuven Avi-Yonah, September 2013.

Executive Summary

This paper proposes to eliminate the U.S. citizenship based taxation and create a consistent exit tax system. The complex web of the current U.S. tax law has made it nearly impossible for all but the most sophisticated U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents (“LPRs”) residing overseas to file complete and accurate tax returns. The proposal should bring consistency, tax simplicity for taxpayers residing outside the U.S., and do so in part by eliminating the U.S. citizenship based tax system, which is unique in the world, dates to the civil war and is inappropriate for the global world we live in.

- Summary of Current Status of the Law

To date, there is no serious and comprehensive proposal to modify the U.S. federal tax law imposing U.S. taxation of the worldwide income of USCs and LPRs residing outside the U.S.

There are also no serious proposals to repeal the current U.S. “expatriation tax” on (1) mark to market income and gains (When does “Covered Expatriate” Status -NOT- matter?) and (2) the 40% tax on covered gifts and inheritances (see, Proposed Regulations for “Covered Gifts” and “Covered Bequests” Issued by Treasury Last Week (Be Careful What You Ask For!)

Part II: C’est la vie Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle! Tax Timing Problems for Former U.S. Citizens is Nothing New – the IRS and the Courts Have Decided Similar Issues in the Past (Pre IRC Section 877A(g)(4))

This is Part II, a follow-on discussion of older U.S. case law and IRS rulings that address how and when individuals are subject to U.S. taxation before and after they assert they are no longer U.S. citizens.

I might point out that I am of the belief that we humans always like to hear the news we want to hear; and/or interpret it in the way we find most beneficial to us. Who doesn’t like good news versus bad news? Whether we (laypeople and tax lawyers alike) interpret Section 877A(g)(4) in any particular way; it is of no real consequence when it is the IRS that will enforce the law and ultimately the Department of Justice, Tax Division who will handle any such case interpreting this provision before a U.S. District Court or the Court of Federal Claims. For those who have not litigated before these Courts and seen how aggressive are the government lawyers in advocating for the government, the following discussion will hopefully be illustrative.

See, Part I: Tax Timing Problems for Former U.S. Citizens is Nothing New – the IRS and the Courts Have Decided Similar Issues in the Past (Pre IRC Section 877A(g)(4)), dated October 16, 2015.

The question is what is the correct date of “relinquishment of citizenship” as defined in the statute; IRC Section 877A(g)(4)? Many argue the law cannot be applied retroactively?

However, the specific case discussed here, did just that; applied the law retroactively to determine U.S. citizenship status of an individual and corresponding tax obligations. This was also in a time of a much simpler tax code with (i) no international information reporting requirements (e.g., IRS Forms 8938, 8858, 5471, 8865, 3520, 3520-A, 926, 8621, etc.), (ii) no Title 31 “FBAR” reporting requirements and (iii) no constant drumbeat by the IRS of international taxpayers and enforcement. See, recent announcement by IRS on Oct. 16, 2015 (one day after tax returns were required to be filed by many) Offshore Compliance Programs Generate $8 Billion; IRS Urges People to Take Advantage of Voluntary Disclosure Programs. However, for cautionary posts on the IRS OVDP and the deceptive numbers published (e.g., “$8 Billion”), see How is the offshore voluntary disclosure program really working? Not well for USCs and LPRs living overseas posted May 10, 2014 and The 2013 GAO Report of the IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, International Tax Journal, CCH Wolters Kluwer, January-February 2014. PDF version here.

Of course, the answer to this question helps determine if and when will the individual be subject to the federal tax laws of the U.S. on their worldwide income and global assets. In the case of Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle (an interesting 1977 appellate opinion from the firs circuit) she had spent little time in the U.S. and had sent a letter in her native language French to the U.S. Department of State, which stated “I have never considered myself to be a citizen of the United States.” This is not unlike many individuals around the world today; at least as of late – in the era of FATCA, who assert they are not a U.S. citizen because they “relinquish[ed] it by the performance of certain expatriating acts with the required “intent” to give up the US citizenship” and did not notify the U.S. federal government.

The Court nevertheless found Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle retroactively subject to U.S. income taxation on her non-U.S. source income (up until she received a certificate of loss of nationality from the Department of State); for specific years even when the immigration law provisions of the day said she was no longer a U.S. citizen during that same retroactive period.

There have been many contemporary commentators who argue an individual does not need to (i) have, (ii) do, or (iii) receive any of the following, and yet still should be able to successfully argue they have shed themselves of U.S. citizenship and hence the obligations of U.S. taxation and reporting on their worldwide income and global assets –

(i) receive a U.S. federal government issued document (e.g., a certificate of loss of nationality “CLN” per 877A(g)(4)(C)),

(ii) receive a cancelation of a naturalized citizen’s certificate of naturalization by a U.S. court (per 877A(g)(4)(D)),

(iii) provide a signed statement of voluntary relinquishment from the individual to the U.S. Department of State (per 877A(g)(4)(B)), or

(iv) provide proof of an in person renunciation before a diplomatic or consular officer of the U.S. (per paragraph (5) of section 349(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1481(a)(5)), in accordance with 877A(g)(4)(C)).

Some older tax cases that interpreted similar concepts are worthy of consideration. They will certainly be in any brief of the attorneys for the U.S. Department of Justice, Tax Division and/or Chief Counsel lawyers for the IRS in any case where the individual challenges that none of the above items are required in their particular case to avoid U.S. taxation and reporting requirements.

The D’Hotelle case is illustrative of the efforts taken by the Department of Justice, Tax Division in collecting U.S. income tax on a naturalized citizen. You will notice they did not take a sympathetic approach to her case. Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle was born in France in 1909 and died in 1968 in France, yet the U.S. government continued to pursue collection of U.S. income taxation on her foreign source income from the Dominican Republic, France and apparently Puerto Rico even after her death during a period of time when she used a U.S. passport. Lucienne D’Hotelle de Benitez Rexach, 558 F.2d 37 (1st Cir.1977). She, not unlike many individuals today, claimed she was not a U.S. citizen – or at least stated “I have never considered myself to be a citizen of the United States.”

Some of the particularly interesting facts relevant to Ms. D’Hotelle, a naturalized citizen, which are relevant to the question of U.S. taxation of citizens, were set forth in the appellate court’s decision as follows:

Lucienne D’Hotelle was born in France in 1909. She became Lucienne D’Hotelle de Benitez Rexach upon her marriage to Felix in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1928. She was naturalized as a United States citizen on December 7, 1942. The couple spent some time in the Dominican Republic, where Felix engaged in harbor construction projects. Lucienne established a residence in her native France on November 10, 1946 and remained a resident until May 20, 1952. During that time s 404(b) of the Nationality Act of 19402 provided that naturalized citizens who returned to their country of birth and resided there for three years lost their American citizenship. On November 10, 1947, after Lucienne had been in France for one year, the American Embassy in Paris issued her a United States passport valid through November 9, 1949. Soon after its expiration Lucienne applied in Puerto Rico for a renewal. By this time she had resided in France for three years.

* * *

On May 20, 1952, the Vice-Consul there signed a Certificate of Loss of Nationality, citing Lucienne’s continuous residence in France as having automatically divested her of citizenship under s 404(b). Her passport . . . was confiscated, cancelled and never returned to her. The State Department approved the certificate on December 23, 1952. Lucienne made no attempt to regain her American citizenship; neither did she affirmatively renounce it.

* * *

Predictably, the United States eventually sought to tax Lucienne for her half of that income. Whether by accident or design, the government’s efforts began in earnest shortly after the Supreme Court invalidated *40 the successor statute4 to s 404(b). In in Schneider v. Rusk, 377 U.S. 163 (1964), the Court held that the distinction drawn by the statute between naturalized and native-born Americans was so discriminatory as to violate due process. In January 1965, about two months after this suit was filed, the State Department notified Lucienne by letter that her expatriation was void under Schneider and that the State Department considered her a citizen. Lucienne replied that she had accepted her denaturalization without protest and had thereafter considered herself not to be an American citizen.

There are other facts that make clear the government was not fond of her husband, the income that he earned and how he managed his and his wife’s assets during and after her death. The Court also discusses at length the fact that she had used a U.S. passport during the years when she alleges she was not a U.S. citizen. The Court goes on to analyze her U.S. citizenship, and the following discussions are illustrative of the ultimate tax consequences.

The government contends that Lucienne was still an American citizen from her third anniversary as a French resident until the day the Certificate of Loss of Nationality was issued in Nice. This case presents a curious situation, since usually it is the individual who claims citizenship and the government which denies it. But pocketbook considerations occasionally reverse the roles. United States v. Matheson, 532 F.2d 809 (2nd Cir.), cert. denied 429 U.S. 823, 97 S.Ct. 75, 50 L.Ed.2d 85 (1976). The government’s position is that under either Schneider v. Rusk, supra, or Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253, 87 S.Ct. 1660, 18 L.Ed.2d 757 (1967), the statute by which Lucienne was denaturalized is unconstitutional and its prior effects should be wiped out. Afroyim held that Congress lacks the power to strip persons of citizenship merely *41 because they have voted in a foreign election. The cornerstone of the decision is the proposition that intent to relinquish citizenship is a prerequisite to expatriation.

411 F.Supp. at 1293. However, the district court went too far in viewing the equities as between Lucienne and the government in strict isolation from broad policy considerations which argue for a generally retrospective application of Afroyim and Schneider to the entire class of persons invalidly expatriated. Cf. Linkletter v. Walker, supra. The rights stemming from American citizenship are so important that, absent special circumstances, they must be recognized even for years past. Unless held to have been citizens without interruption, persons wrongfully expatriated as well as their offspring might be permanently and unreasonably barred from important benefits.6 Application of Afroyim or Schneider is generally appropriate.* * *

During the interval from late 1949 to mid-1952, Lucienne was unaware that she had been automatically denaturalized.

* * *