FATCA

Form 8854 Filing: TIGTA Report Reveals Compliance Gap

See the “TIGTA Report”. Read it here: More Enforcement and a Centralized Compliance Effort Are Required for Expatriation Provisions

Does TIGTA have the Answer: to the Question – How many former U.S. citizens and long-term lawful permanent residents have filed and should have filed IRS Form 8854?

The short answer to the question above – is NO!

The government does not know how many IRS Forms 8854 should have been filed.

Note the total numbers of 8854 returns filed as reported in Figure 2 of the TIGTA Report were less than 25,000 during a ten year period. This report focuses really only on former U.S. citizens (“USC”) who have renounced their citizenship. Not on lawful permanent residents (“LPRs), which during that same ten year period there were around 200,000 who filed USCIS Form I-407.

* How Many Individuals Should have Filed Form 8854?

W-8s for U.S. Citizens Abroad: Filing False Information with Non-U.S. Banks

Individuals who do not specialize in U.S. federal tax law, often have little detailed understanding of the U.S. federal “Chapter 3” (long-standing law regarding withholding taxes on non-resident aliens and foreign corporations and foreign trusts) and “Chapter 4” (the relatively new withholding tax regime known as the “Foreign Account Tax  Compliance Act”) rules.

Compliance Act”) rules.

Indeed, plenty of U.S. tax law professionals (CPAs, tax attorneys and enrolled agents) do not understand well the interplay between these two different withholding regimes –

- 26 U.S. Code Chapter 3 – WITHHOLDING OF TAX ON NONRESIDENT ALIENS AND FOREIGN CORPORATIONS

- 26 U.S. Code Chapter 4 – TAXES TO ENFORCE REPORTING ON CERTAIN FOREIGN ACCOUNTS

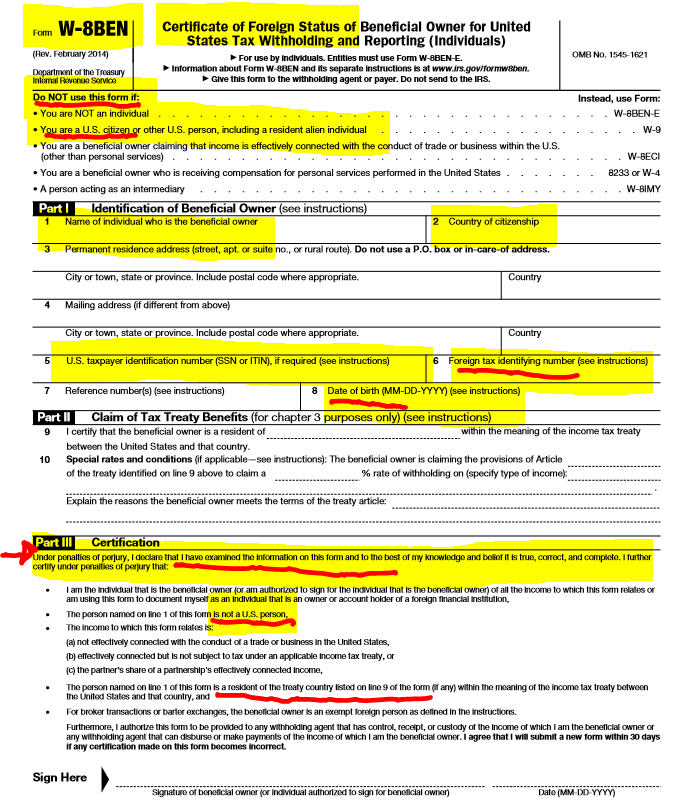

Plus, the IRS forms have been significantly modified over the years; with increasing factual representations that must be made by individuals who sign the forms under penalty of perjury. They are complex and not well understood. For instance, the older 2006 IRS Form W-8BEN for companies was one page in length and required relatively little information be provided.

The entire form is reproduced here; indicating how foreign taxpayer information was optional and generally there was no requirement to obtain a U.S. taxpayer identification number. It was governed exclusively by Chapter 3 and the regulations that had been  extensively produced back in the early 2000s.

extensively produced back in the early 2000s.

The forms were even easier before those regulations (see old IRS Form 1001). No taxpayer identification numbers were ever required and virtually no supporting information regarding reduced tax treaty rates on U.S. sources of income.

Life was simple back then – compared to today!

The one thing all of these forms have in common is that all information was provided and certified under penalty of perjury. Current day IRS Forms W-8s can typically be completed accurately by experts who understand the complex web of rules. Plus, multiple versions of W-8s exist today; most running some 8+ pages in length.

See the potpourri of current day W-8 forms –

Making certifications under penalty of perjury are more complex, the more and more factual information that is being certified. If I certify the dog I see in front of me is “white and black” that is not a complex certification, if I see the dog and see the “white and black”. If the dog also has some brown coloring, my certification would necessarily not be false.

However, if I have to certify as to the colors of each dog in a pack of 8 dogs (and each and every color that each dog is/was), that becomes a much more complicated certification.

That’s my analogy for the old IRS Forms W-8s and the current day IRS Forms W-8s.

Compare that form, of just 10 years ago, with what is required and must be certified to under current law. It can be daunting.

Now to the rub. Individuals who certify erroneously or falsely, can run a risk that the government asserts such signed certification was done intentionally. I have seen it happen in real cases; even though the individual layperson (particularly those who speak little to no English and live outside the U.S.) typically has little understanding of these rules. They typically sign the documents presented to them by the third party; usually the banks and other financial institutions.

The U.S. federal tax law has a specific crime, for making a false statement or signing a false tax return or other document – which is known as the perjury statute (IRC Section 7206(1)). This is a criminal statute, not civil. Some people are also under the misunderstanding that a false tax return needs to be filed. The statute is much broader and includes “. . . any statement . . . or other document . . . “.

(1) Declaration under penalties of perjury

Willfully makes and subscribes any return, statement, or other document, which contains or is verified by a written declaration that it is made under the penalties of perjury, and which he does not believe to be true and correct as to every material matter; or . . .

Therefore, if a U.S. citizen living overseas (or anywhere) signs IRS Form W-8BEN (or the bank’s substitute form, which requests the same basic information), that signature under penalty of perjury will necessarily be a false statement, as a matter of law. Why? By definition, the statute says a U.S. citizen is a “United States person” as that technical term is defined in IRC Section 7701(a)(30)(A). Accordingly, IRS Form W-8BEN, must only be signed by an individual who is NOT a “United States person”; who necessarily cannot be a United States citizen. To repeat, a United States citizen is included in the definition of a “United States person.” Plus, the form itself, as highlighted at the beginning of the form, warns against any U.S. citizen signing such form.

Accordingly, if a U.S. citizen were to sign IRS Form W-8BEN which I have seen banks erroneously request of their clients, they run the risk that the U.S. federal government will argue that such signatures and filing of false information with the bank was intentional and therefore criminal under IRC Section 7206(1). See a prior post, What could be the focal point of IRS Criminal Investigations of Former U.S. Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents?

Indeed, criminal cases are not simple, and I am not aware of any single criminal case that hinged exclusively on a false IRS Form W-8BEN. However, I have seen cases, where the government has alleged the U.S. born individual must have signed the form intentionally, knowing the information was false. It’s a question of proof and of course U.S. citizens wherever they reside, should take care to never sign an IRS Form W-8BEN as an individual certifying they are not a “United States person”; even if they think they are not a U.S. person

For further background information on this topic, see a prior post: FATCA Driven – New IRS Forms W-8BEN versus W-8BEN-E versus W-9 (etc. etc.) for USCs and LPRs Overseas – It’s All About Information and More Information

Foreign Government Receives a “FATCA Christmas Gift” from IRS: 1 Gigabyte of U.S. Financial Information

The last post discussed how the director of the Mexican tax administration was critical of the U.S. federal government for not providing FATCA information on U.S. financial accounts. See, Foreign Government Criticizes U.S. Government for  NOT Providing FATCA IGA Information on Their Taxpayers with U.S. Accounts, dated December 14, 2015.

NOT Providing FATCA IGA Information on Their Taxpayers with U.S. Accounts, dated December 14, 2015.

The automatic exchange of bank and financial information is driven by the U.S. Treasury driven Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA).

As a follow-up, the Mexican newspaper Reforma reported on the 17th of December that the U.S. just provided Mexico’s treasury with a gigabyte of Mexican taxpayer information regarding U.S. financial and bank accounts. See, Entrega EU un gigabyte a Hacienda, dated Dec 17, 2015.

This news comes on the heals of the earlier criticism by the Commissioner of the Mexican IRS (SAT – Servicio de  Administración Tributaria (SAT)), Mr. Aristóteles Núñez Sánchez. The Reforma article quotes Óscar Molina Chié (who is in charge of the large taxpayers division at SAT) generously regarding how and what information was provided by the U.S. federal government.

Administración Tributaria (SAT)), Mr. Aristóteles Núñez Sánchez. The Reforma article quotes Óscar Molina Chié (who is in charge of the large taxpayers division at SAT) generously regarding how and what information was provided by the U.S. federal government.

Finally, the article emphasized that Mexico has sent the IRS information regarding Mexican bank accounts of U.S. citizens.

The question is how much Mexican bank and financial information has actually been provided by SAT of the hundreds of thousands (if not more than 1 million) dual national taxpayers, who are citizens of both Mexico and the U.S.? See, Where the IRS will likely look overseas: USCs are Millions Yet U.S. Tax Returns are Just a Few Hundred Thousand, dated January 28, 2015.

WSJ Asks the Question: Is the IRS Undercounting Americans Renouncing U.S. Citizenship?

Is the IRS Undercounting Americans Renouncing U.S. Citizenship?, posted Sept. 16, 2015.

The names of U.S. citizens who have renounced is published quarterly pursuant to IRC Section  6039G. See, prior related posts: 1,426 Individuals Give Up Passport: Record Number of U.S. Citizens Renouncing: Quarter 3 for 2015, October 30, 2015.

6039G. See, prior related posts: 1,426 Individuals Give Up Passport: Record Number of U.S. Citizens Renouncing: Quarter 3 for 2015, October 30, 2015.

No one knows for certain if the IRS (including the IRS per some of my conversations) is getting complete data from the Department of State regarding each name and individual.

The graph I have prepared shows the number of names reported quarterly as I track all reported names quarterly that related to clients and non-clients. The latest cumulative amounts for 2015 (which does not include the 4th quarter) shows 3,221 thus far in the year. If there is close to 1,400 as was the case for the last quarter, the total will be a record – by a bunch; i.e., close to 5,000 renunciations for the year.

Anecdotally, I have seen renunciations surge in our practice, largely as U.S. citizens residing around the world (typically in the “Accidental American” category) learn about the long arm of the U.S. tax law by way of their local financial institutions and reporting and documents requested as part of FATCA. See, Why Most U.S. Citizens Residing Overseas Haven’t a Clue about the Labyrinth of U.S. Taxation and Bank and Financial Reporting of Worldwide Income and Assets, posted Nov. 2, 2015.

None of this answers the question of whether there is under-reporting of the names? Indeed, the question will likely not be answered without more information provided by the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Treasury (i.e., the IRS officers responsible for issuing the names and report in the Federal Register).

The government is also likely to reject issuing information on these details to individuals and their advisers as part of a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request. I have had similar requests rejected by the government under the so called “Exemption 7(E)” of FOIA. See,

Part II: C’est la vie Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle! Tax Timing Problems for Former U.S. Citizens is Nothing New – the IRS and the Courts Have Decided Similar Issues in the Past (Pre IRC Section 877A(g)(4))

This is Part II, a follow-on discussion of older U.S. case law and IRS rulings that address how and when individuals are subject to U.S. taxation before and after they assert they are no longer U.S. citizens.

I might point out that I am of the belief that we humans always like to hear the news we want to hear; and/or interpret it in the way we find most beneficial to us. Who doesn’t like good news versus bad news? Whether we (laypeople and tax lawyers alike) interpret Section 877A(g)(4) in any particular way; it is of no real consequence when it is the IRS that will enforce the law and ultimately the Department of Justice, Tax Division who will handle any such case interpreting this provision before a U.S. District Court or the Court of Federal Claims. For those who have not litigated before these Courts and seen how aggressive are the government lawyers in advocating for the government, the following discussion will hopefully be illustrative.

See, Part I: Tax Timing Problems for Former U.S. Citizens is Nothing New – the IRS and the Courts Have Decided Similar Issues in the Past (Pre IRC Section 877A(g)(4)), dated October 16, 2015.

The question is what is the correct date of “relinquishment of citizenship” as defined in the statute; IRC Section 877A(g)(4)? Many argue the law cannot be applied retroactively?

However, the specific case discussed here, did just that; applied the law retroactively to determine U.S. citizenship status of an individual and corresponding tax obligations. This was also in a time of a much simpler tax code with (i) no international information reporting requirements (e.g., IRS Forms 8938, 8858, 5471, 8865, 3520, 3520-A, 926, 8621, etc.), (ii) no Title 31 “FBAR” reporting requirements and (iii) no constant drumbeat by the IRS of international taxpayers and enforcement. See, recent announcement by IRS on Oct. 16, 2015 (one day after tax returns were required to be filed by many) Offshore Compliance Programs Generate $8 Billion; IRS Urges People to Take Advantage of Voluntary Disclosure Programs. However, for cautionary posts on the IRS OVDP and the deceptive numbers published (e.g., “$8 Billion”), see How is the offshore voluntary disclosure program really working? Not well for USCs and LPRs living overseas posted May 10, 2014 and The 2013 GAO Report of the IRS Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, International Tax Journal, CCH Wolters Kluwer, January-February 2014. PDF version here.

Of course, the answer to this question helps determine if and when will the individual be subject to the federal tax laws of the U.S. on their worldwide income and global assets. In the case of Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle (an interesting 1977 appellate opinion from the firs circuit) she had spent little time in the U.S. and had sent a letter in her native language French to the U.S. Department of State, which stated “I have never considered myself to be a citizen of the United States.” This is not unlike many individuals around the world today; at least as of late – in the era of FATCA, who assert they are not a U.S. citizen because they “relinquish[ed] it by the performance of certain expatriating acts with the required “intent” to give up the US citizenship” and did not notify the U.S. federal government.

The Court nevertheless found Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle retroactively subject to U.S. income taxation on her non-U.S. source income (up until she received a certificate of loss of nationality from the Department of State); for specific years even when the immigration law provisions of the day said she was no longer a U.S. citizen during that same retroactive period.

There have been many contemporary commentators who argue an individual does not need to (i) have, (ii) do, or (iii) receive any of the following, and yet still should be able to successfully argue they have shed themselves of U.S. citizenship and hence the obligations of U.S. taxation and reporting on their worldwide income and global assets –

(i) receive a U.S. federal government issued document (e.g., a certificate of loss of nationality “CLN” per 877A(g)(4)(C)),

(ii) receive a cancelation of a naturalized citizen’s certificate of naturalization by a U.S. court (per 877A(g)(4)(D)),

(iii) provide a signed statement of voluntary relinquishment from the individual to the U.S. Department of State (per 877A(g)(4)(B)), or

(iv) provide proof of an in person renunciation before a diplomatic or consular officer of the U.S. (per paragraph (5) of section 349(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1481(a)(5)), in accordance with 877A(g)(4)(C)).

Some older tax cases that interpreted similar concepts are worthy of consideration. They will certainly be in any brief of the attorneys for the U.S. Department of Justice, Tax Division and/or Chief Counsel lawyers for the IRS in any case where the individual challenges that none of the above items are required in their particular case to avoid U.S. taxation and reporting requirements.

The D’Hotelle case is illustrative of the efforts taken by the Department of Justice, Tax Division in collecting U.S. income tax on a naturalized citizen. You will notice they did not take a sympathetic approach to her case. Ms. Lucienne D’Hotelle was born in France in 1909 and died in 1968 in France, yet the U.S. government continued to pursue collection of U.S. income taxation on her foreign source income from the Dominican Republic, France and apparently Puerto Rico even after her death during a period of time when she used a U.S. passport. Lucienne D’Hotelle de Benitez Rexach, 558 F.2d 37 (1st Cir.1977). She, not unlike many individuals today, claimed she was not a U.S. citizen – or at least stated “I have never considered myself to be a citizen of the United States.”

Some of the particularly interesting facts relevant to Ms. D’Hotelle, a naturalized citizen, which are relevant to the question of U.S. taxation of citizens, were set forth in the appellate court’s decision as follows:

Lucienne D’Hotelle was born in France in 1909. She became Lucienne D’Hotelle de Benitez Rexach upon her marriage to Felix in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1928. She was naturalized as a United States citizen on December 7, 1942. The couple spent some time in the Dominican Republic, where Felix engaged in harbor construction projects. Lucienne established a residence in her native France on November 10, 1946 and remained a resident until May 20, 1952. During that time s 404(b) of the Nationality Act of 19402 provided that naturalized citizens who returned to their country of birth and resided there for three years lost their American citizenship. On November 10, 1947, after Lucienne had been in France for one year, the American Embassy in Paris issued her a United States passport valid through November 9, 1949. Soon after its expiration Lucienne applied in Puerto Rico for a renewal. By this time she had resided in France for three years.

* * *

On May 20, 1952, the Vice-Consul there signed a Certificate of Loss of Nationality, citing Lucienne’s continuous residence in France as having automatically divested her of citizenship under s 404(b). Her passport . . . was confiscated, cancelled and never returned to her. The State Department approved the certificate on December 23, 1952. Lucienne made no attempt to regain her American citizenship; neither did she affirmatively renounce it.

* * *

Predictably, the United States eventually sought to tax Lucienne for her half of that income. Whether by accident or design, the government’s efforts began in earnest shortly after the Supreme Court invalidated *40 the successor statute4 to s 404(b). In in Schneider v. Rusk, 377 U.S. 163 (1964), the Court held that the distinction drawn by the statute between naturalized and native-born Americans was so discriminatory as to violate due process. In January 1965, about two months after this suit was filed, the State Department notified Lucienne by letter that her expatriation was void under Schneider and that the State Department considered her a citizen. Lucienne replied that she had accepted her denaturalization without protest and had thereafter considered herself not to be an American citizen.

There are other facts that make clear the government was not fond of her husband, the income that he earned and how he managed his and his wife’s assets during and after her death. The Court also discusses at length the fact that she had used a U.S. passport during the years when she alleges she was not a U.S. citizen. The Court goes on to analyze her U.S. citizenship, and the following discussions are illustrative of the ultimate tax consequences.

The government contends that Lucienne was still an American citizen from her third anniversary as a French resident until the day the Certificate of Loss of Nationality was issued in Nice. This case presents a curious situation, since usually it is the individual who claims citizenship and the government which denies it. But pocketbook considerations occasionally reverse the roles. United States v. Matheson, 532 F.2d 809 (2nd Cir.), cert. denied 429 U.S. 823, 97 S.Ct. 75, 50 L.Ed.2d 85 (1976). The government’s position is that under either Schneider v. Rusk, supra, or Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253, 87 S.Ct. 1660, 18 L.Ed.2d 757 (1967), the statute by which Lucienne was denaturalized is unconstitutional and its prior effects should be wiped out. Afroyim held that Congress lacks the power to strip persons of citizenship merely *41 because they have voted in a foreign election. The cornerstone of the decision is the proposition that intent to relinquish citizenship is a prerequisite to expatriation.

411 F.Supp. at 1293. However, the district court went too far in viewing the equities as between Lucienne and the government in strict isolation from broad policy considerations which argue for a generally retrospective application of Afroyim and Schneider to the entire class of persons invalidly expatriated. Cf. Linkletter v. Walker, supra. The rights stemming from American citizenship are so important that, absent special circumstances, they must be recognized even for years past. Unless held to have been citizens without interruption, persons wrongfully expatriated as well as their offspring might be permanently and unreasonably barred from important benefits.6 Application of Afroyim or Schneider is generally appropriate.* * *

During the interval from late 1949 to mid-1952, Lucienne was unaware that she had been automatically denaturalized.

* * *