Tax Policy

Form 8854 Filing: TIGTA Report Reveals Compliance Gap

See the “TIGTA Report”. Read it here: More Enforcement and a Centralized Compliance Effort Are Required for Expatriation Provisions

Does TIGTA have the Answer: to the Question – How many former U.S. citizens and long-term lawful permanent residents have filed and should have filed IRS Form 8854?

The short answer to the question above – is NO!

The government does not know how many IRS Forms 8854 should have been filed.

Note the total numbers of 8854 returns filed as reported in Figure 2 of the TIGTA Report were less than 25,000 during a ten year period. This report focuses really only on former U.S. citizens (“USC”) who have renounced their citizenship. Not on lawful permanent residents (“LPRs), which during that same ten year period there were around 200,000 who filed USCIS Form I-407.

* How Many Individuals Should have Filed Form 8854?

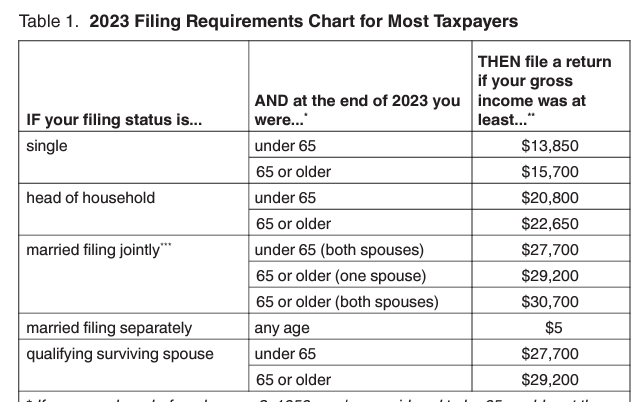

When do I (as a resident) meet the gross income thresholds that require me to file a U.S. income tax return? Updated for 2023 Income Thresholds

In 2014, this blog explained the income thresholds relevant for filing tax returns during those years. However, the tax reform implemented in 2018, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), brought significant changes to who is required to file tax returns based on income thresholds. So, when exactly do I reach the gross income thresholds that necessitate filing a U.S. income tax return? Old Post (2014)

These thresholds differ significantly from those in 2014 due to the TCJA passed in 2017.

That blog post detailed specific requirements applicable only to U.S. resident individual taxpayers:

Any USC individual (and any LPR who does not live in a country with a U.S. income tax treaty) is obligated under the U.S. federal tax law to file a federal income tax return IRS Form Form 1040 if they meet minimum thresholds of income. The thresholds are low, and are reached once the gross income is at least the sum of (i) the “exemption” amount (currently US$3,900 per exemption) and (ii) the “standard deduction” amount.

Accordingly, even if a USC or LPR has even a modest sum of “gross income”, which equates to at least US$10,000 (in whatever currency earned), the USC or LPR will probably have a U.S. tax return filing requirement.

Several significant developments have occurred since the publication of that blog post. First, the federal tax reform primarily applicable for the 2018 tax year, the The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), substantially altered various tax concepts. Specifically, the TCJA eliminated the concept of “personal exemptions” for the taxpayer, spouse, and dependents. These were previously used to calculate income thresholds determining whether a U.S. resident taxpayer had to file a tax return or not. However, they are no longer applicable. The standard deduction is now key to determine who is required to file.

A recent federal report from Congressional Research Service (CRS Report explains -Nov. 2023): Under the TCJA, basic standard deduction amounts in 2018 were nearly doubled to $12,000 for single filers, $18,000 for head of household filers, and $24,000 for married joint filers. These amounts were annually adjusted for inflation after 2018. In 2024, these amounts are $14,600, $21,900, and $29,200, respectfully.

Hence, for U.S. residents, the filing thresholds have increased substantially for those required to file U.S. tax returns: $14,600 for single filers, $21,900 for head of household filers, and $29,200 for married joint filers for the 2024 tax year.

Non-residents have a completely different rule as to when they are required to file U.S. non-resident tax returns (1040NR), which will be discussed in a later blog. A non-resident can have as little as say US$1,500 of income sourced from the United States and have an obligation to file a tax return. Totally different thresholds and totally different rules are applicable.

Part II: “Neither Confirm nor Deny the Existence of the TECs Database”: IRS Using the TECs Database to Track Taxpayers Movements – and Assets

Part II: This is a follow-up to the federal government’s database known as “TECS” (Treasury Enforcement Communication System)that is now operated by the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”). The IRS uses it to track travel, trips, movement and even asset movements (e.g., wire transfers) by U.S. citizen taxpayers; including those residing outside the U.S.

See, “Neither Confirm nor Deny the Existence of the TECs data”: IRS Using the TECs Database to Track Taxpayers Movements –, posted Dec. 13, 2014.

This previous post described how the U.S. federal government uses the TECS to locate assets and travel patterns of U.S. citizens; specifically outside the U.S. The IRS trains their employees to (1) Not discuss TECS with taxpayers; (2) Neither confirm nor deny existence of TECS; (3) Keep in separate “Confidential” envelope; and (4) Stamp documents as “OFFICIAL USE ONLY”

The image in this post reflects a page from IRS training materials for their employees; e.g., revenue agents (those individuals who audit taxpayers and determine tax deficiencies and the like), revenue officers (those individuals who work on collecting taxes owed or alleged to be owed) and chief counsel attorneys (those individuals who litigate tax cases against taxpayers); among other IRS employees.

Frankly, there is not a lot of detailed law about how and when the IRS can use TECS or other tracking techniques of individuals and their assets. There are no tax cases (at least none that I am aware of) where the Courts have tried to impose limits on the use and  methods of the federal government in collecting this type of TECS information. Indeed, there are specific provisions granting broad use of taxpayer information when the government alleges there is a “terrorist incident, threat, or activity” as that term is defined in IRC Section § 6103.

methods of the federal government in collecting this type of TECS information. Indeed, there are specific provisions granting broad use of taxpayer information when the government alleges there is a “terrorist incident, threat, or activity” as that term is defined in IRC Section § 6103.

On the other hand, there are important laws about how the IRS cannot generally disclose taxpayer information. For instance, see the same code section IRC Section § 6103 for wrongful disclosures of taxpayers’ information. That statute makes it a violation (even a criminal violation in certain willful circumstances) to disclose taxpayer information in “most” (or at least many) circumstances. The statute is comprehensive and there is a lot of case law interpreting various provisions. A good overview of the statute can be found in the Criminal Tax Manual for the Department of Justice, Tax Division – Chapter 42.00

A recent case (United States v. Garrity, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 66372 (D. Conn. 2016), discussed in Jack Townsend’s blog, was one where the IRS had disclosed the name of a deceased taxpayer Paul G. Garrity, Sr. regarding his foreign (non-U.S.) accounts. The disclosure included IRS investigation techniques that were disclosed as part of a FOIA request, which ultimately made it to the public. This was found to be disclosure of return information as defined by IRC Section § 6103. However, the Court there found that there was no violation of the statute by the IRS, as the taxpayer was deceased by the time the claim was brought by the estate. The government made a Title 31 FBAR penalty assessment of over US$1M including interest and penalties that is still pending.

It seems to me that the use of the TECS database by the IRS and Section 6103 are a bit like two heads of a coin. It all deals with taxpayer information and what rights, if any do taxpayers have to protect their personal and financial information – especially where it can (purposefully or inadvertently – e.g., through a data breach/hacking) be released to the public.

There are many unanswered questions as there has been little to no litigation regarding how and when the TECS database can and should be used.

Does the government have any limits on its use?

This ultimately becomes more of a policy discussion about how and to what extent can/should the federal government have and use and collect personal financial and travel information of individuals (particularly for tax purposes)?

As FATCA data collection has now allowed exchanges of millions of records, these questions in my view take on even greater importance. See 21 Dec 2015 post, Foreign Government Receives a “FATCA Christmas Gift” from IRS: 1 Gigabyte of U.S. Financial Information.

See a prior related post, 19 Jan 2014 – Should IRS use Department of Homeland Security to Track Taxpayers Overseas Re: Civil (not Criminal) Tax Matters? The IRS works with Department of Homeland Security with TECs Database to Track Movement of Taxpayers

Key Concepts of Senate Finance Chairman Hatch’s Proposal Re: “Non-Resident U.S. Citizens”

The complete report can be located at the Senate Finance Committee website at Comprehensive Tax Reform for 2015 and Beyond – Senate Republican Staff –

The crucial policy considerations are set out in the report. The key paragraph of the report is reproduced here:

The principle idea is to impose U.S. income taxation on U.S. sources only for U.S. citizens residing overseas. The report leaves many unanswered questions. One of those questions is how to integrate the “expatriation tax rules” into such a concept? There is one sentence addressing this point, which contemplates the “mark to market exit tax” will continue as part of the law, if such a proposal were to become law.

The report does not discuss how the U.S. transfer tax system (U.S. estate, gift and generation skipping transfer taxes) might be reformed. Current law, imposes worldwide U.S. estate, gift and generation skipping transfer taxes on the worldwide assets of a U.S. citizen.

Time will tell if such a proposal gets any political traction in Congress or at the White House.