Collateral Consequences – Non-Tax

Is the “Mark to Market” Expatriation Tax Unconstitutional? – through the Prism of Moore

No Court in the land has explicitly ruled on whether the “mark to market” tax under Section 877A is unconstitutional. However, many international tax minds (myself included) have doubted the ability of Congress to levy a tax on unrealized wealth in light of Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920) and the language of the amendment ratified in 1913 to the Constitution.

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

16th Amendment of the Constitution [emphasis added]:

One of the exceptional international tax minds, Professor Reuven S. Avi-Yonah has been writing a lot about this issue after submitting an amicus brief along with Professor Bret Wells to the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) in the Moore case which was decided last week. Moore v. United States, No. 22-800 (06/20/2024). Moore was not about “expatriation taxes” but rather a “mandatory repatriation tax” (“MRT”) under Section 965.

Moore argued some of the fundamental issues that lie at the core, in my view, of whether Congress has the legal authority to impose taxation (as an income tax) based upon the increased value of assets as of the date, the individual becomes a “covered expatriate”. How does the individual have any income (see, Eisner v. Macomber) by merely holding and having the same assets on the day prior to “expatriation” as the day after? No sales, no exchanges, no dispositions, no transfers, no gifting, etc. – and yet 26 U. S. C. § 877A imposes taxation on “income.”

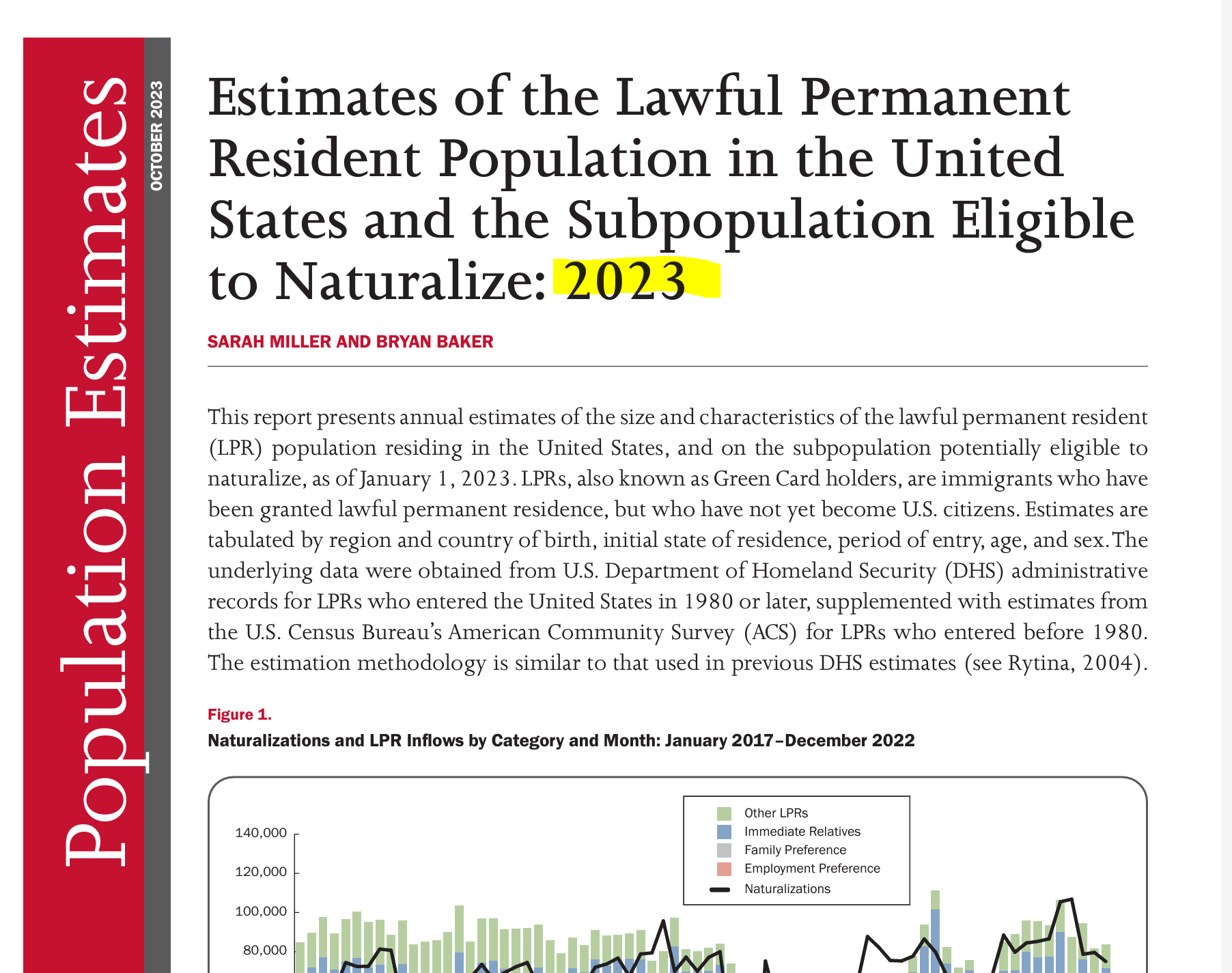

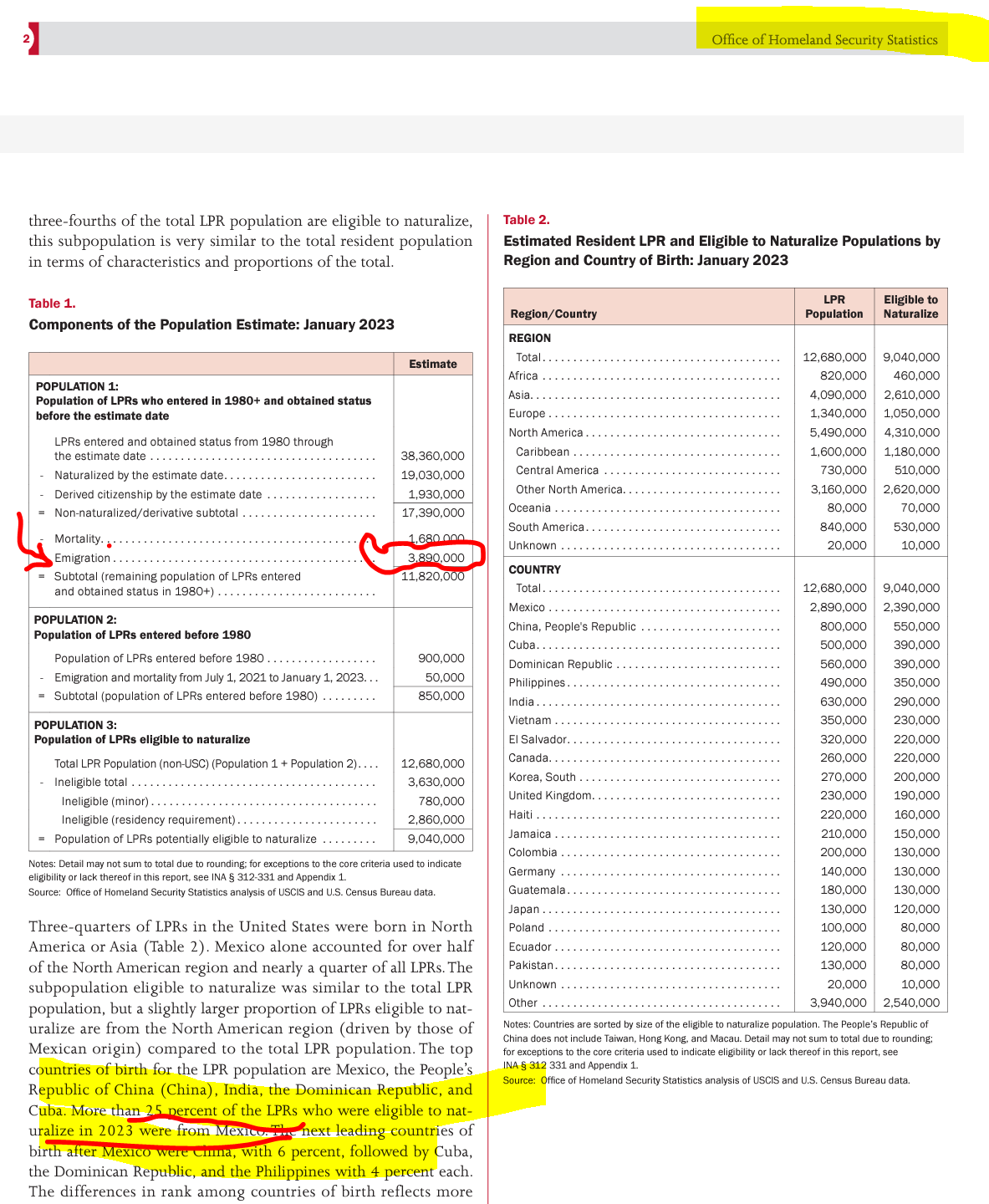

Countries From Which Viewers Read Posts – Tax-Expatriation.com – First Week of 2024 (Which Ones are Tax Treaty Countries?) – Applying the “Escape Hatch”

The whole idea of the “escape hatch” for tax treaties is an excellent way of explaining how and when tax treaty law applies in different circumstances. Importantly, the U.S. federal government cannot deny an individual (or presumably a company either) from properly applying the law of a tax treaty – even if they “gave [an] untimely notice of his treaty position “. See further comments at the end of this post and the District Court’s opinion here – Aroeste v United States – Order (Nov 2023). Meanwhile, see below the 22 countries from where global readers viewed Tax-Expatriation.com during the first full week of 2024.

Below is the list of 22 countries (including the United States) from where readers hailed, who read Tax-Expatriation.com during the first week of 2024. All, but Brazil, Croatia, Nigeria, the United Arab Emirates, Colombia, Kenya and Bermuda have income tax treaties with the United States.

This means that all other individuals are connected with the following 14 countries that have tax treaties with the United States:

- Mexico

- India

- Canada

- United Kingdom

- Switzerland

- Australia

- China

- Spain

- Turkey

- Germany

- Japan

- Romania

- Portugal

- Netherlands

Further, all individuals who might have never formally abandoned their lawful permanent residency (“green card”), maybe never filed specific IRS tax forms, and yet reside in one of these fourteen (14) treaty countries could be eligible for the application and the specific benefits of international income tax treaty law. This, along the lines of the decision in Aroeste v United States (Nov. 2023). In addition, there could be other tax treaty benefits applicable to those individuals in these fourteen countries depending upon where are their assets, what type of income they have, where does the income come from, and where do they reside.

The tax treaty rights discussed here are established by law, as elucidated by the Federal District Court in Aroeste v United States (Nov. 2023). The Court determined that the IRS cannot simply assert an individual’s ineligibility for treaty law provisions based solely on the failure to file specific IRS forms within the government-defined “timely” period. The Court emphasized that there is no automatic waiver of treaty benefits as a matter of law, while acknowledging: “. . . Aroeste gave untimely notice of his treaty position. . .” For specific excerpts from the opinion, please refer to the highlighted portions below. To access the complete opinion, please consult Aroeste v United States – Order (Nov 2023).

* * * * * * * * *

B. Whether Aroeste Did Not Waive the Benefits of the Treaty Applicable to Residents of Mexico and Notified the Secretary of Commencement of Such Treatment.

To establish Mexican residency under the Treaty, and thus avoid the reporting requirements of “United States persons,” Aroeste must have filed a timely income tax return as a non-resident (Form 1040NR) with a Form 8833, Treaty-Based Return Position Case 3:22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC Document 90 Filed 11/20/23 PageID.2722 Page 8 of 17 9 22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC Disclosure Under Section 6114 or 7701(b). Indeed, Aroeste did not submit Form 8833 to notify the IRS of his desired treaty position for the years 2012 and 2013 until October 12, 2016, when he submitted an amended tax return for both years at issue. (Id.) The Government asserts that because Aroeste did not timely submit these forms, he cannot establish that he notified the IRS of his desire to be treated solely as a resident of Mexico and not waive the benefits of the Treaty. (Id. at 4.) The Government relies upon United States v. Little, 828 Fed. App’x 34 (2d Cir. 2020) (“Little II”), a criminal appeal in which the court held a lawful permanent resident of a foreign country was a “‘resident alien’ or ‘person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States’ with an obligation to file an FBAR.” Id. at 38 (quoting 31 C.F.R. § 1010.350(a), (b)(2)).

In response, Aroeste asserts that while he agrees with the Government that I.R.C. § 6114 requires disclosure of a treaty position, he disagrees as to the consequences for a taxpayer’s failure to timely file the disclosure. (Doc. No. 75-1 at 6.) While the Government asserts the failure to timely file Forms 1040NR and 8833 deprives individuals of the Treaty benefits provided, Aroeste argues instead that I.R.C. § 6712 provides explicit consequences for failure to comply with § 6114. Specifically, § 6712 states that “[i]f a taxpayer fails to meet the requirements of section 6114, there is hereby imposed a penalty equal to $1,000 . . . on each such failure.” I.R.C. § 6712(a). Based on the foregoing, Aroeste argues the taxpayer does not lose the benefits or application of the treaty law.1 (Doc. No. 75-1 at 6.) In United States v. Little, 12-cr-647 (PKC), 2017 WL 1743837, at *5 (S.D. N.Y. 1 Aroeste further asserts that published agency guidance, letter rulings, and technical advice support his position. (Doc. No. 75-1 at 7.) For example, in 2007, an IRS agent sought advice from IRS Counsel asking, “Do we have legal authority to deny a tax treaty because Form 8833 is not attached or the treaty is claimed on the wrong Form (1040EZ or 1040)?” Legal Advice Issued to Program Managers During 2007 Document Number 2007-01188, IRS. IRS Counsel responded, “No, you cannot deny treaty benefits if the taxpayer is entitled to them. You may impose a penalty of $1,000 under section 6712 of the Code on an individual who is obligated to file and does not.” Id. As to this, the Court finds it has no precedential value under I.R.C. § 6110(k)(3), which states that “a written determination may not be used or cited as precedent.” See Amtel, Inc. v. United States, 31 Fed. Cl. 598, 602 (1994) (“The [Internal Revenue] Code specifically precludes [plaintiff] and the court from using or citing a technical advice memorandum as precedent.”) Case 3:22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC Document 90 Filed 11/20/23 PageID.2723 Page 9 of 17 10 22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC May 3, 2017) (“Little I”), a criminal case for the plaintiff’s willful failure to file tax returns, the court stated the plaintiff’s same argument “that the failure to take a Treaty position can result only in a financial penalty also lacks merit. 26 U.S.C. § 6712(c) expressly states that ‘[t]he penalty imposed by this section shall be in addition to any other penalty imposed by law.’” (emphasis added).

I have been consulted over the years by other taxpayers which are cited now as published decisions by the government and the Federal District Court (Southern District of California). These cases are referenced and cited in my own most recent case of Aroeste v United States (Nov. 2023).

However, in Little I, the plaintiff never attempted to take a treaty position. Next, in Shnier v. United States, 151 Fed. Cl. 1, 21 (2020), the court denied the plaintiffs’ claims for relief based on tax treaties because they failed to disclose a treaty based position on their tax returns pursuant to I.R.C. § 6114 “and did not attempt to cure this omission in their briefing[.]” Although the plaintiffs in Shnier were naturalized U.S. citizens who attempted to recover their income taxes under I.R.C § 1297, the court’s brief discussion of I.R.C. § 6114 in relation to a treaty-based position is instructive that an untimely notice of a treaty position does not bar the individual from taking such position. Moreover, in Pekar v. C.I.R., 113 T.C. 158 (1999), the court noted that a taxpayer who fails to disclose a treaty-based position as required by § 6114 is subject to the $1,000 penalty, but stated “there is no indication that this failure estops a taxpayer from taking such a position.” Id. at 161 n.5.2 The Court agrees with Aroeste.

Although Aroeste gave untimely notice of his treaty position, the Court finds this does not waive the benefits of the Treaty as asserted by the Government. Rather, I.R.C. § 6712 provides the consequences for failure to comply with I.R.C. § 6114, namely a penalty of $1,000 for each failure to meet § 6114’s requirements of disclosing a treaty position.

* * * * * * * * *

For individuals living in any of these 14 tax treaty countries (or any of the total 67 income tax treaty countries), the key takeaway is that, based on their specific circumstances, they might be eligible to leverage the international tax treaty principles outlined in the Aroeste v United States case (Nov. 2023). The forthcoming post will pose questions for consideration by the potentially millions of individuals affected by these rules of law.

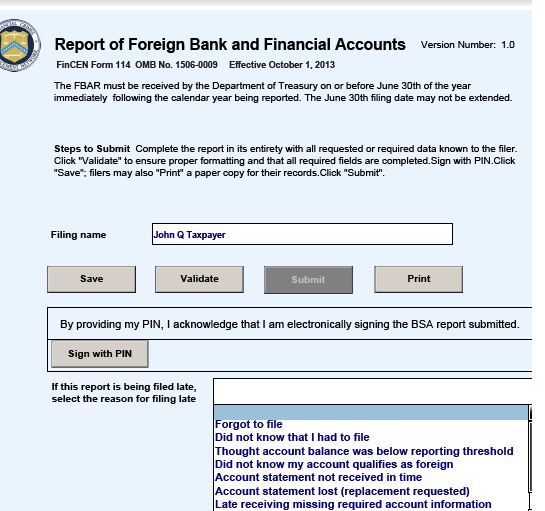

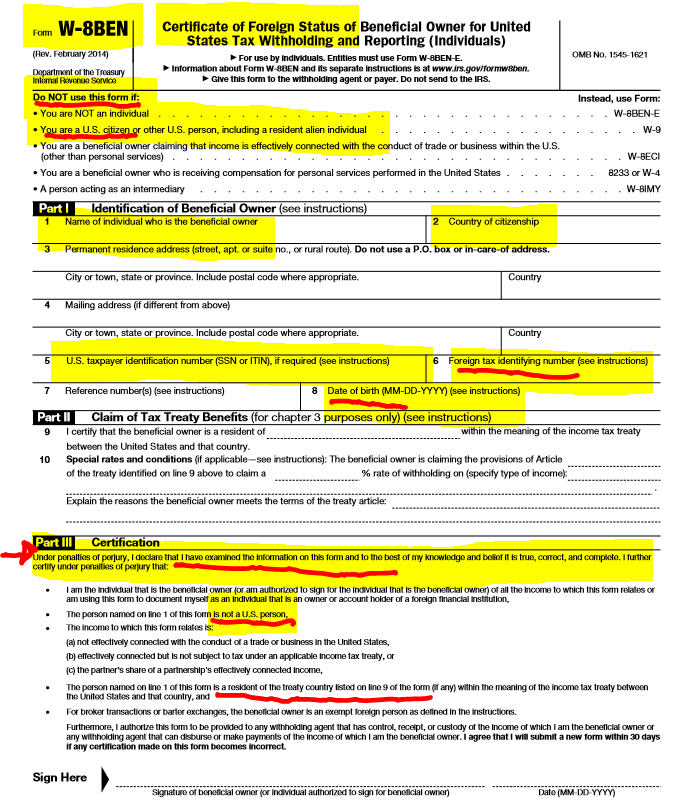

W-8s for U.S. Citizens Abroad: Filing False Information with Non-U.S. Banks

Individuals who do not specialize in U.S. federal tax law, often have little detailed understanding of the U.S. federal “Chapter 3” (long-standing law regarding withholding taxes on non-resident aliens and foreign corporations and foreign trusts) and “Chapter 4” (the relatively new withholding tax regime known as the “Foreign Account Tax  Compliance Act”) rules.

Compliance Act”) rules.

Indeed, plenty of U.S. tax law professionals (CPAs, tax attorneys and enrolled agents) do not understand well the interplay between these two different withholding regimes –

- 26 U.S. Code Chapter 3 – WITHHOLDING OF TAX ON NONRESIDENT ALIENS AND FOREIGN CORPORATIONS

- 26 U.S. Code Chapter 4 – TAXES TO ENFORCE REPORTING ON CERTAIN FOREIGN ACCOUNTS

Plus, the IRS forms have been significantly modified over the years; with increasing factual representations that must be made by individuals who sign the forms under penalty of perjury. They are complex and not well understood. For instance, the older 2006 IRS Form W-8BEN for companies was one page in length and required relatively little information be provided.

The entire form is reproduced here; indicating how foreign taxpayer information was optional and generally there was no requirement to obtain a U.S. taxpayer identification number. It was governed exclusively by Chapter 3 and the regulations that had been  extensively produced back in the early 2000s.

extensively produced back in the early 2000s.

The forms were even easier before those regulations (see old IRS Form 1001). No taxpayer identification numbers were ever required and virtually no supporting information regarding reduced tax treaty rates on U.S. sources of income.

Life was simple back then – compared to today!

The one thing all of these forms have in common is that all information was provided and certified under penalty of perjury. Current day IRS Forms W-8s can typically be completed accurately by experts who understand the complex web of rules. Plus, multiple versions of W-8s exist today; most running some 8+ pages in length.

See the potpourri of current day W-8 forms –

Making certifications under penalty of perjury are more complex, the more and more factual information that is being certified. If I certify the dog I see in front of me is “white and black” that is not a complex certification, if I see the dog and see the “white and black”. If the dog also has some brown coloring, my certification would necessarily not be false.

However, if I have to certify as to the colors of each dog in a pack of 8 dogs (and each and every color that each dog is/was), that becomes a much more complicated certification.

That’s my analogy for the old IRS Forms W-8s and the current day IRS Forms W-8s.

Compare that form, of just 10 years ago, with what is required and must be certified to under current law. It can be daunting.

Now to the rub. Individuals who certify erroneously or falsely, can run a risk that the government asserts such signed certification was done intentionally. I have seen it happen in real cases; even though the individual layperson (particularly those who speak little to no English and live outside the U.S.) typically has little understanding of these rules. They typically sign the documents presented to them by the third party; usually the banks and other financial institutions.

The U.S. federal tax law has a specific crime, for making a false statement or signing a false tax return or other document – which is known as the perjury statute (IRC Section 7206(1)). This is a criminal statute, not civil. Some people are also under the misunderstanding that a false tax return needs to be filed. The statute is much broader and includes “. . . any statement . . . or other document . . . “.

(1) Declaration under penalties of perjury

Willfully makes and subscribes any return, statement, or other document, which contains or is verified by a written declaration that it is made under the penalties of perjury, and which he does not believe to be true and correct as to every material matter; or . . .

Therefore, if a U.S. citizen living overseas (or anywhere) signs IRS Form W-8BEN (or the bank’s substitute form, which requests the same basic information), that signature under penalty of perjury will necessarily be a false statement, as a matter of law. Why? By definition, the statute says a U.S. citizen is a “United States person” as that technical term is defined in IRC Section 7701(a)(30)(A). Accordingly, IRS Form W-8BEN, must only be signed by an individual who is NOT a “United States person”; who necessarily cannot be a United States citizen. To repeat, a United States citizen is included in the definition of a “United States person.” Plus, the form itself, as highlighted at the beginning of the form, warns against any U.S. citizen signing such form.

Accordingly, if a U.S. citizen were to sign IRS Form W-8BEN which I have seen banks erroneously request of their clients, they run the risk that the U.S. federal government will argue that such signatures and filing of false information with the bank was intentional and therefore criminal under IRC Section 7206(1). See a prior post, What could be the focal point of IRS Criminal Investigations of Former U.S. Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents?

Indeed, criminal cases are not simple, and I am not aware of any single criminal case that hinged exclusively on a false IRS Form W-8BEN. However, I have seen cases, where the government has alleged the U.S. born individual must have signed the form intentionally, knowing the information was false. It’s a question of proof and of course U.S. citizens wherever they reside, should take care to never sign an IRS Form W-8BEN as an individual certifying they are not a “United States person”; even if they think they are not a U.S. person

For further background information on this topic, see a prior post: FATCA Driven – New IRS Forms W-8BEN versus W-8BEN-E versus W-9 (etc. etc.) for USCs and LPRs Overseas – It’s All About Information and More Information

Part I: New TIGTA Report to Congress (Sept 30) Has International Emphasis on Collecting Taxes Owed by “International Taxpayers”: Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA)

TIGTA’s Semiannual Reports – Today’s Report with International Considerations – Part I

The Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Department of Justice (Tax Division) are the “soldiers” on the ground used to enforce U.S. federal tax law. They interpret the law, in no small part based upon the expertise and input of the myriad of experts in the U.S. Treasury, IRS and DOJ.

However, there are outside forces which oftentimes seem to have an “over-sized” influence on how, when and what priorities are identified in the IRS and DOJ. One of those powers of course is the Administration which makes up the Treasury Department and the very Department of Justice. The green book proposals of the Treasury and different policy proposals are an example. The other organization, within the Executive Branch is the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA).

TIGTA is the sort of “watch dog” over the IRS that independently reviews the work undertaken and often times questions that work and the IRS’ efforts. Per its own website it describes itself as:

The Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) was established in January 1999 in accordance with the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 (RRA 98) to provide independent oversight of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) activities. As mandated by RRA 98, TIGTA assumed most of the responsibilities of the IRS’ former Inspection Service.

TIGTA is separate and apart from the Taxpayer Advocate Service (“TAS”). See, excerpts of TAS reports here.

Another important influence is the Congress. See a prior post from September 2014 on this topic: How Congressional Hearings (Particularly In the Senate) Drive IRS and Justice Department Behavior