Corollary Tax Consequences

Countries From Which Viewers Read Posts – Tax-Expatriation.com – First Week of 2024 (Which Ones are Tax Treaty Countries?) – Applying the “Escape Hatch”

The whole idea of the “escape hatch” for tax treaties is an excellent way of explaining how and when tax treaty law applies in different circumstances. Importantly, the U.S. federal government cannot deny an individual (or presumably a company either) from properly applying the law of a tax treaty – even if they “gave [an] untimely notice of his treaty position “. See further comments at the end of this post and the District Court’s opinion here – Aroeste v United States – Order (Nov 2023). Meanwhile, see below the 22 countries from where global readers viewed Tax-Expatriation.com during the first full week of 2024.

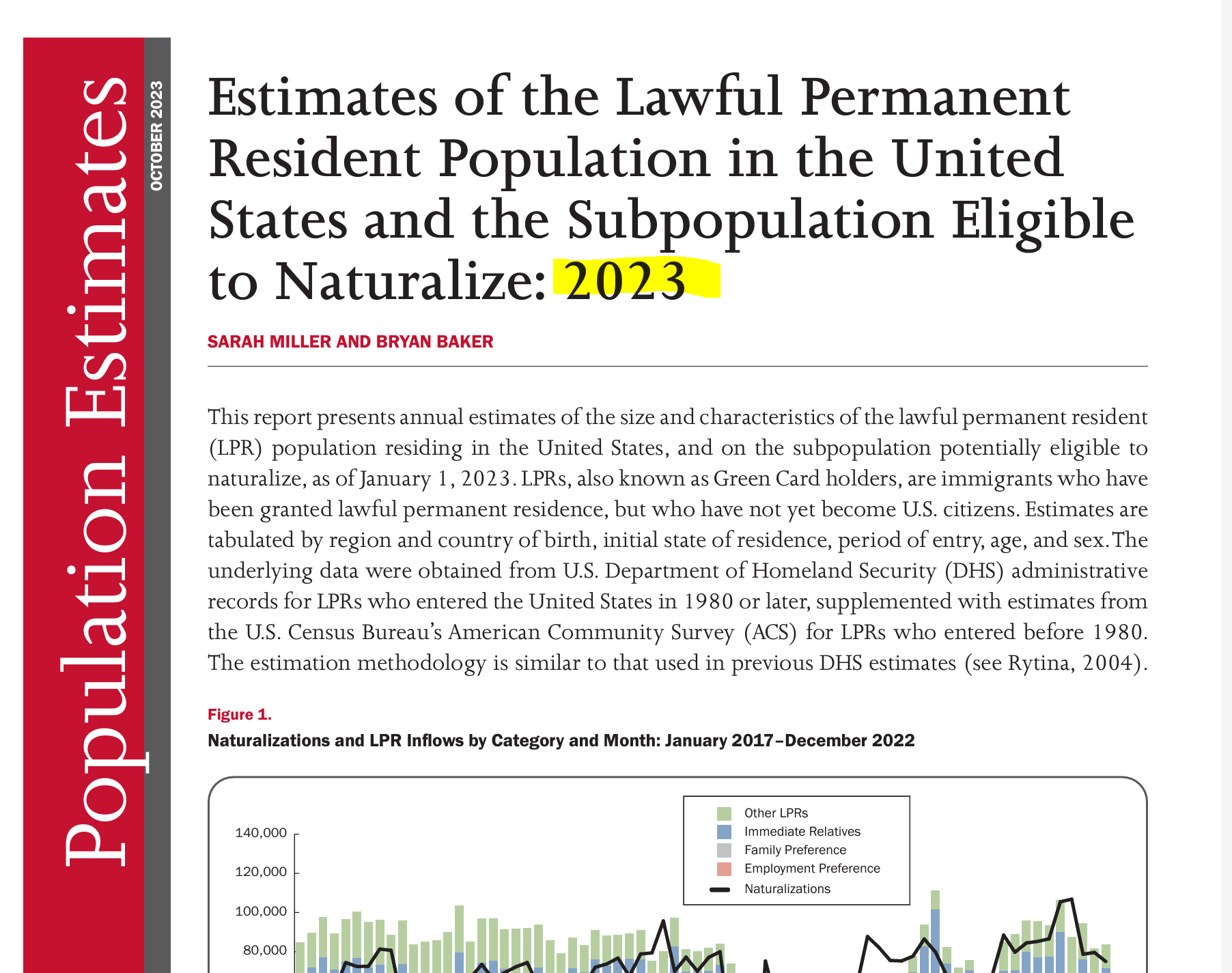

Below is the list of 22 countries (including the United States) from where readers hailed, who read Tax-Expatriation.com during the first week of 2024. All, but Brazil, Croatia, Nigeria, the United Arab Emirates, Colombia, Kenya and Bermuda have income tax treaties with the United States.

This means that all other individuals are connected with the following 14 countries that have tax treaties with the United States:

- Mexico

- India

- Canada

- United Kingdom

- Switzerland

- Australia

- China

- Spain

- Turkey

- Germany

- Japan

- Romania

- Portugal

- Netherlands

Further, all individuals who might have never formally abandoned their lawful permanent residency (“green card”), maybe never filed specific IRS tax forms, and yet reside in one of these fourteen (14) treaty countries could be eligible for the application and the specific benefits of international income tax treaty law. This, along the lines of the decision in Aroeste v United States (Nov. 2023). In addition, there could be other tax treaty benefits applicable to those individuals in these fourteen countries depending upon where are their assets, what type of income they have, where does the income come from, and where do they reside.

The tax treaty rights discussed here are established by law, as elucidated by the Federal District Court in Aroeste v United States (Nov. 2023). The Court determined that the IRS cannot simply assert an individual’s ineligibility for treaty law provisions based solely on the failure to file specific IRS forms within the government-defined “timely” period. The Court emphasized that there is no automatic waiver of treaty benefits as a matter of law, while acknowledging: “. . . Aroeste gave untimely notice of his treaty position. . .” For specific excerpts from the opinion, please refer to the highlighted portions below. To access the complete opinion, please consult Aroeste v United States – Order (Nov 2023).

* * * * * * * * *

B. Whether Aroeste Did Not Waive the Benefits of the Treaty Applicable to Residents of Mexico and Notified the Secretary of Commencement of Such Treatment.

To establish Mexican residency under the Treaty, and thus avoid the reporting requirements of “United States persons,” Aroeste must have filed a timely income tax return as a non-resident (Form 1040NR) with a Form 8833, Treaty-Based Return Position Case 3:22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC Document 90 Filed 11/20/23 PageID.2722 Page 8 of 17 9 22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC Disclosure Under Section 6114 or 7701(b). Indeed, Aroeste did not submit Form 8833 to notify the IRS of his desired treaty position for the years 2012 and 2013 until October 12, 2016, when he submitted an amended tax return for both years at issue. (Id.) The Government asserts that because Aroeste did not timely submit these forms, he cannot establish that he notified the IRS of his desire to be treated solely as a resident of Mexico and not waive the benefits of the Treaty. (Id. at 4.) The Government relies upon United States v. Little, 828 Fed. App’x 34 (2d Cir. 2020) (“Little II”), a criminal appeal in which the court held a lawful permanent resident of a foreign country was a “‘resident alien’ or ‘person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States’ with an obligation to file an FBAR.” Id. at 38 (quoting 31 C.F.R. § 1010.350(a), (b)(2)).

In response, Aroeste asserts that while he agrees with the Government that I.R.C. § 6114 requires disclosure of a treaty position, he disagrees as to the consequences for a taxpayer’s failure to timely file the disclosure. (Doc. No. 75-1 at 6.) While the Government asserts the failure to timely file Forms 1040NR and 8833 deprives individuals of the Treaty benefits provided, Aroeste argues instead that I.R.C. § 6712 provides explicit consequences for failure to comply with § 6114. Specifically, § 6712 states that “[i]f a taxpayer fails to meet the requirements of section 6114, there is hereby imposed a penalty equal to $1,000 . . . on each such failure.” I.R.C. § 6712(a). Based on the foregoing, Aroeste argues the taxpayer does not lose the benefits or application of the treaty law.1 (Doc. No. 75-1 at 6.) In United States v. Little, 12-cr-647 (PKC), 2017 WL 1743837, at *5 (S.D. N.Y. 1 Aroeste further asserts that published agency guidance, letter rulings, and technical advice support his position. (Doc. No. 75-1 at 7.) For example, in 2007, an IRS agent sought advice from IRS Counsel asking, “Do we have legal authority to deny a tax treaty because Form 8833 is not attached or the treaty is claimed on the wrong Form (1040EZ or 1040)?” Legal Advice Issued to Program Managers During 2007 Document Number 2007-01188, IRS. IRS Counsel responded, “No, you cannot deny treaty benefits if the taxpayer is entitled to them. You may impose a penalty of $1,000 under section 6712 of the Code on an individual who is obligated to file and does not.” Id. As to this, the Court finds it has no precedential value under I.R.C. § 6110(k)(3), which states that “a written determination may not be used or cited as precedent.” See Amtel, Inc. v. United States, 31 Fed. Cl. 598, 602 (1994) (“The [Internal Revenue] Code specifically precludes [plaintiff] and the court from using or citing a technical advice memorandum as precedent.”) Case 3:22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC Document 90 Filed 11/20/23 PageID.2723 Page 9 of 17 10 22-cv-00682-AJB-KSC May 3, 2017) (“Little I”), a criminal case for the plaintiff’s willful failure to file tax returns, the court stated the plaintiff’s same argument “that the failure to take a Treaty position can result only in a financial penalty also lacks merit. 26 U.S.C. § 6712(c) expressly states that ‘[t]he penalty imposed by this section shall be in addition to any other penalty imposed by law.’” (emphasis added).

I have been consulted over the years by other taxpayers which are cited now as published decisions by the government and the Federal District Court (Southern District of California). These cases are referenced and cited in my own most recent case of Aroeste v United States (Nov. 2023).

However, in Little I, the plaintiff never attempted to take a treaty position. Next, in Shnier v. United States, 151 Fed. Cl. 1, 21 (2020), the court denied the plaintiffs’ claims for relief based on tax treaties because they failed to disclose a treaty based position on their tax returns pursuant to I.R.C. § 6114 “and did not attempt to cure this omission in their briefing[.]” Although the plaintiffs in Shnier were naturalized U.S. citizens who attempted to recover their income taxes under I.R.C § 1297, the court’s brief discussion of I.R.C. § 6114 in relation to a treaty-based position is instructive that an untimely notice of a treaty position does not bar the individual from taking such position. Moreover, in Pekar v. C.I.R., 113 T.C. 158 (1999), the court noted that a taxpayer who fails to disclose a treaty-based position as required by § 6114 is subject to the $1,000 penalty, but stated “there is no indication that this failure estops a taxpayer from taking such a position.” Id. at 161 n.5.2 The Court agrees with Aroeste.

Although Aroeste gave untimely notice of his treaty position, the Court finds this does not waive the benefits of the Treaty as asserted by the Government. Rather, I.R.C. § 6712 provides the consequences for failure to comply with I.R.C. § 6114, namely a penalty of $1,000 for each failure to meet § 6114’s requirements of disclosing a treaty position.

* * * * * * * * *

For individuals living in any of these 14 tax treaty countries (or any of the total 67 income tax treaty countries), the key takeaway is that, based on their specific circumstances, they might be eligible to leverage the international tax treaty principles outlined in the Aroeste v United States case (Nov. 2023). The forthcoming post will pose questions for consideration by the potentially millions of individuals affected by these rules of law.

Survey of the Law of Expatriation from 2002: Department of Justice Analysis (Not a Tax Discussion)

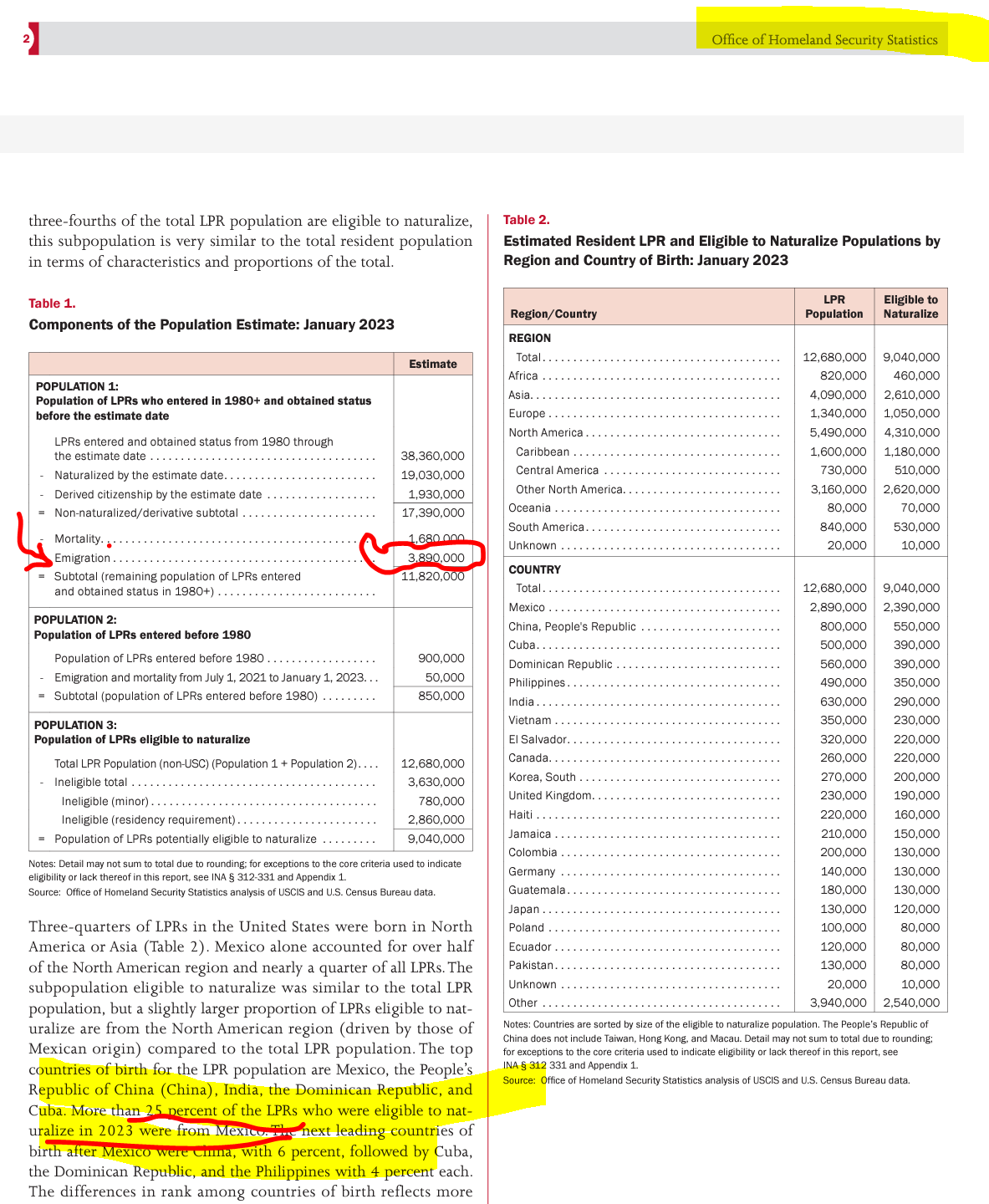

Most discussions regarding renunciation/relinquishment of U.S. citizenship are highly focused towards the U.S. federal tax consequences. Today, the focus is on a 2002 report prepared by the DOJ for the Solicitor General, who supervises and conducts government litigation in the United States Supreme Court.

The report is found here, and I have highlighted some key excerpts: Survey of the Law of Expatriation: Department of Justice Analysis:

* * *

What is the 10 year “Collection Statute” and Why is it Suspended for USCs and LPRs Overseas?

There are different periods of time the federal tax law sets forth to protect both the taxpayer and the government. In short, after a certain period of time (assuming numerous conditions are satisfied), neither (i) the government can take action to assess or recover taxes, or (ii) the taxpayer can demand a tax refund.

This concept is known as the “statute of limitations” and is a concept deeply imbedded throughout U.S. law, not just taxation law.

There are two key aspects for how and when taxes are levied by the IRS. First, there is the “assessment” part, which helps determine a tax is owing in the first place. There have been chapters of tax treatises written on how and when an assessment is valid. A tax return is a “self-assessment”. See, for instance, the CCH® Expert Treatise Library: Tax Practice and Procedure, and its chapter on Assessment and Collection.

The IRS can also make an assessment through a so-called “substitute return.” See, How the IRS Can file a “Substitute Return” for those USCs and LPRs Residing Overseas.

The focus of this post, is on the second aspect; the “collection” part of how the IRS collects upon a final tax assessment.

There is a 10 year collection statute of limitations imposed upon the IRS. See IRC Section 6502.

The general rule, is that the IRS cannot wait forever to collect against a taxpayer for the amount of taxes owing. If the taxes are not collected within this 10 year period, the general rule is that the IRS cannot continue to attempt to collect the taxes.

However, there is a huge exception in the 10 year collection statutory law, which does not apply when the individual is physically outside the United States for a continuous period of at least six months. See, IRC Section 6503(c). This means that any USC or LPR residing predominantly outside the U.S. will have this 10 year collection statute suspended in favor of the government.

In other words, the IRS will be able to indefinitely use its collection efforts to lien and levy assets of the taxpayer, when she is living outside the U.S. The only way to “re-start” the collection statute, is for the individual to travel to the U.S. and not stay outside the U.S. for more than a six month period. Obviously, for those who live outside the U.S., this will typically be impractical, if not impossible, to live several month continuous periods within the U.S.

Finally, traveling to the U.S., can raise additional issues for the overseas USC or LPR who has taxes owing to the IRS. See, Should IRS use Department of Homeland Security to Track Taxpayers Overseas Re: Civil (not Criminal) Tax Matters? The IRS works with Department of Homeland Security with TECs Database to Track Movement of Taxpayers

See also, U.S. Enforcement/Collection of Taxes Overseas against USCs and LPRs – Legal Limitations

More on FATCA Driven IRS Forms, specifically including IRS Form W-8BEN-E ~ It’s All About Information and More Information

The lives of United States Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents living outside the U.S. has necessarily become more complicated due to FATCA.

Previous posts discussed unintended consequences of FATCA. See, Part 2 – Unintended Consequences of FATCA – for USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S.

Also, see, Part 1- Unintended Consequences of FATCA – for USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S.

– One of the most significant unintended consequence, is that the U.S. federal government (the IRS, the Treasury Department, or  Congress) never initially even contemplated USCs and LPRs living overseas. In other words, the group targeted were U.S. resident individuals who were evading taxes through foreign financial institutions. I say this, based upon extensive conversations I have had with ex-government officials and some government officials who were involved in the original policy discussions.

Congress) never initially even contemplated USCs and LPRs living overseas. In other words, the group targeted were U.S. resident individuals who were evading taxes through foreign financial institutions. I say this, based upon extensive conversations I have had with ex-government officials and some government officials who were involved in the original policy discussions.

Currently, the IRS has revised or created the following new tax forms as a result of FATCA (all in  the English language), which can be located at the IRS website at FATCA – Current Alerts and Other News:

the English language), which can be located at the IRS website at FATCA – Current Alerts and Other News:

Importantly, none of these forms are in other key languages such as Spanish, French, Mandarin, Cantonese, Portuguese, etc. Imagine the daunting nature of completing these complex forms just in English when English is your first language, let alone completing them when you speak little to no English.

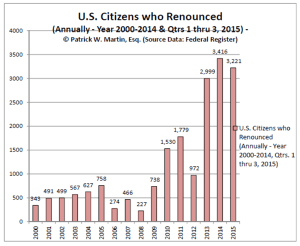

As the financial and account information of U.S. citizens and LPRs at financial institutions worldwide is now being collected to be reported in 2015 to the IRS under FATCA, a better understanding of FATCA forms is required. A follow-up post will specifically discuss how financial and account information of non-U.S. shareholders and owners of foreign corporations, companies and foreign trusts will also  indirectly be reported to the IRS, when there is a “substantial U.S. owner.”

indirectly be reported to the IRS, when there is a “substantial U.S. owner.”

A detailed discussion of how and when this information will be released to the IRS will be explained in a follow-up discussion of a passive “non-financial foreign entity” (“NFFE”) which will typically be a foreign corporation (non-U.S.), companies and foreign trusts.

This information is set forth and requested in Parts XXX and XXIX on the last page of IRS Form W-8BEN-E on page 8. These items are highlighted here in yellow reflecting the information requested.

A follow-up post will explain what is a “passive” NFFE and what information is required to be reported per the form. For a better understanding of the importance of signing a document “under penalty of perjury” see Certifying Under Penalty of Perjury – Meeting the Requirements of Title 26 for Preceding 5 Taxable Years.

529 College Plans – Funded by Former USCs and LPRs (“Long-Term” LPRs)

There is a basic tax planning opportunity for U.S. taxpayers who wish to fund the costs of higher education for family or friends. These are referred to as “529 Plans” with reference to the tax code section – IRC Section 529. In short, a 529 trust is established and funded with contributions for the benefit of named beneficiaries.

The principle benefit of a 529 plan, is that the income earned from the investments inside the 529 trust fund are exempt from U.S. income taxation.

There are multiple plans that are operated by various institutions, principally in conjunction with various States in the United States. Qualifying higher education expenses also apply to about 350 non-U.S. institutions that currently qualify for distributions out of a 529 Plan; e.g., University of Cambridge, University of Dublin Trinity College, University of Edinburgh, University of Oslo, The University of York, University of Wollongong, etc.

Unfortunately, non-U.S. citizens who are not resident in the U.S. generally are not eligible to establish and form a new 529 plan.

These “529 Plans” fall expressly into the category of a “specified tax deferred account” under the law. See, IRC Section 877A(e)(2).

In short, the law causes the entire amount in the 529 Plan to be treated as distributed to the “covered expatriate” the day before the expatriation date, although no early distribution tax will apply. If a 529 Plan has $500,000, that will represent taxable income to the “covered expatriate” to the extent of the tax-free growth in the plan. For instance, if the individual funded $200,000 into this plan, in this example, and he or she is subject to the 39.6% tax rate upon “expatriation”, this means there will be US$118,800 less to pay for college and universities (i.e., $500,000 less the $200,000 invested; leaving $300,000 X 39.6% = US$118,800 of tax).

This is yet another example, of how and why it is so important to avoid “covered expatriate” status; if permitted by the law in any particular circumstances. See, Certification Requirement of Section 877(a)(2)(C) – (5 Years of Tax Compliance) and Important Timing Considerations per the Statute, also see Can the Certification Requirement of Section 877(a)(2)(C) be Satisfied “After the Fact”?

Careful thought should be taken for the range of considerations and U.S. tax consequences that can befall a former USC or long-term LPR.

U.S. Tax Court Rules Against Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) in Abrahamsen

The U.S. Tax Court, in an opinion written by Judge Lauber (Abrahamsen v. Commissioner) placed much legal tax significance on the immigration form I-508 that Ms. Abrahamsen signed.

The Court noted this form, I-508, Waiver of Rights, Privileges, Exemptions and Immunities (Under Section 247(b) of the INA) specifically provides that the non-U.S. citizen “waive all rights, privileges, exemptions and immunities which would otherwise accrue to [her] under any law or executive order by reason of [her] occupational status.”

In that case, the individual was a Finnish citizen who eventually applied for lawful permanent residency. The immigration forms were not related to any specific tax form, such as the new IRS Forms W-8BEN; see, IRS Releases New IRS Form W8-BEN. * U.S. citizens and LPRs beware of completing such form at the request of a third party.

The takeaway from this opinion, is that individuals need to be aware of how signing a particular form (that is not a tax form) can have adverse tax consequences. In this case, the Court ruled that she had waived her benefits to IRC Section 893 by signing immigration Form I-508. The opinion of the Tax Court raises an interesting legal question about how signing a form (I-508) can seem to override the statutory protection granted which provides protection to a qualifying “. . . employee [who] is not a citizen of the United States . . . “

Signing various tax forms can cause even greater risks for non-citizen taxpayers; e.g., IRS Form W-9 versus W-8BEN. See, FATCA Driven – New IRS Forms W-8BEN versus W-8BEN-E versus W-9 (etc. etc.) for USCs and LPRs Overseas – It’s All About Information and More Information*

Fortunately for the taxpayer in the Abrahamsen case, she was not subject to the Section 6662 accuracy related penalty (“negligence” penalty) assessed by the IRS.

A subsequent post will analyze some potential U.S. tax consequences for individuals who sign immigration Form I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status

IRA Distributions – (Counter-intuitive Results) U.S. Tax Consequences to Former USCs and Long Term Residents (LPRs)

IRA Distributions – (Counter-intuitive Results) U.S. Tax Consequences to Former USCs and Long Term Residents (LPRs)

Those USCs who have renounced citizenship (or who are contemplating renunciation) and those LPRs who (were/are/will) fall into the category of “long-term residents” who have qualified retirement accounts, known as “Individual Retirement Arrangement” (“IRAs”) have special considerations to consider under IRC Sections 877, et. seq. For more details on how IRAs work and the deduction limits, see the IRS website explanation.

In short, if an individual is a “covered expatriate” upon renunciation (or LPR abandonment), they will generally be subject to U.S. income taxation on the entire amount of the IRA (along with all other assets with unrealized gains), reduced by the exemption amount (currently US$680,000 for the year 2014).

Unfortunately, it is fairly easy to become a “covered expatriate” even if the asset or tax liability tests are not satisfied, simply if the individual fails to satisfy the certification requirement under Section 877(a)(2)(C). There are multiple posts that address this important certification requirement of Section 877(a)(2)(C), irrespective of how poor or how few of assets might be held by the individual. See, Certification Requirement of Section 877(a)(2)(C) – (5 Years of Tax Compliance) and Important Timing Considerations per the Statute, also see Can the Certification Requirement of Section 877(a)(2)(C) be Satisfied “After the Fact”?

Plus, the topic is covered yet further in More on “PFICs” and their Complications for USCs and LPRs Living Outside the U.S. -(What if there are No Records?)

Generally “covered expatriate” status is to be avoided, give the various adverse tax consequences. See, for instance, Why “covered expat” (“covered expatriate”) status matters, even if you have no assets! The “Forever Taint”!

However, since the U.S. tax law is complex and oftentimes full of unintended consequences, there may be times when “covered expatriate” status is desirable in any particular circumstance. I have seen and advised on several; including scenarios, where some planning steps can help get a much better U.S. tax result in various cases.

Assume a former USC does not meet the certification requirement (e.g., since they neglected to properly file a complete and accurate IRS Form 8854, or they otherwise did not comply with Title 26 for one or more of the five years preceding the renunciation/abandonment). Further, let us assume, she has an IRA with a total value of US$1.4M and all of her other assets have no unrealized gain (e.g., Euros in a bank in Europe and an apartment she purchased in her country of residence in Europe that continues to have depressed real estate prices). These other assets, the apartment and Euros are US$500,000 in value; hence, less than the US$2M net worth threshold. However, we will assume she did not timely comply with the certification requirements under the law.

In such an “unfortunate” case, she would have to accelerate all of the income (gain) from her IRA in the year she has her “date of expatriation”. This would cause a U.S. federal income tax liability of about US$260,000 that would become immediately due and payable. This amount is calculated as follows: US$1.4M total IRA, less the $680,000 exclusion amount, for a total taxable income of about $720,000 (which will generate an approximate US$260,000 income tax for someone who is not married filing jointly. This represents an effective tax rate of approximately 36% on the taxable income portion (US$260,000/US$720,000). Remember, however, $680,000 escapes taxation under the exclusion amount. Hence, the effective tax rate on the entire IRA portion is actually only about 18.6% in this case. This amount is calculated as total IRA income of US$1.4M against tax of US$260,000 (i.e., $260,000/$1.4M= 18.6%).

An 18.6% tax rate is generally a very “attractive” U.S. individual income tax rate for those who have high amounts of income, as is this case with US$1.4M.

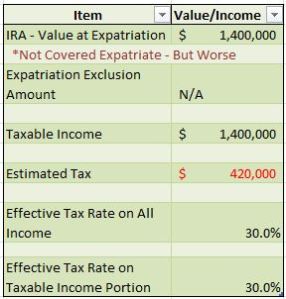

If instead, she is not a “covered expatriate” at the time she renounces her citizenship in 2014 (as she did comply with the certification requirements and otherwise would not meet the $2M net worth and her average annual net income tax liability for the preceding 5 years did not exceed $157,000) she would have a very different tax result. In short, she would not have to accelerate the entire tax liability. That sounds like good news, until one considers the U.S. tax rate on future IRA distributions to her after she ceases to be a U.S. citizen. Absent, an income tax treaty, she would have a 30% tax withheld at source (i.e., by the U.S. payer – trustee of the IRA) on each distribution made. If all US$1.4M is distributed out in one lump sum, there will be a tax of US$420,00 (US$1.4M X 30%); much more than the $260,000 for the “covered expatriate” scenario above. See calculations in this table:

Also, if she prefers to defer the IRA distributions (e.g., to make 14 annual distributions of US$100,000), she will have the same 30% tax withheld on each payment; hence, a total tax of US$420,00.

Obviously, a 30% tax is much worse than an 18.6% tax. Accordingly, this is a scenario where an individual may prefer to be a “covered expatriate” as opposed to avoiding such status. A bunch of factual analysis and strategic considerations would need to be considered in her case (e..g, where are her future heirs, what other income might she receive, will she receive any future gifts of inheritances herself, etc. etc.?).

Indeed, in this particular case, I can imagine a scenario (if accompanied by some focused tax planning), she could pay no more than a total effective tax rate of 12.2% on her income. Of course, 12.2% is better than 18.6% and 30%.

Finally, there is one more important wrinkle that can modify these results yet further; a particular income tax treaty with the U.S. that has a specific tax result that is better than the statutory 30% rate on distributions from an IRA to a non-resident alien. The U.S. has numerous income tax treaties with numerous countries, almost all of which have different terms and conditions. See, Countries with U.S. Income Tax Treaties & Lawful Permanent Residents (“Oops – Did I Expatriate”?)